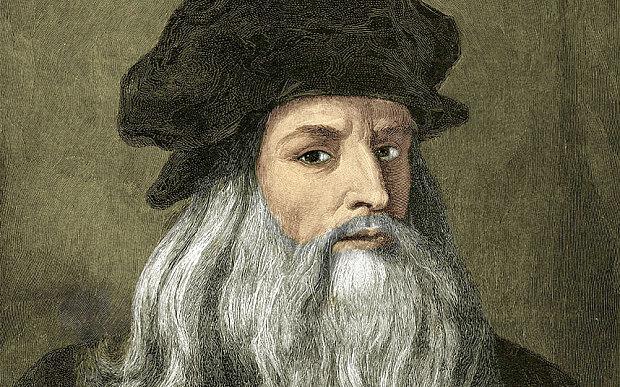

Is there no end to da Vinci’s talent? Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, after 1510, by Francesco Melzi. Public Domain

Old masters rarely come more venerable (and venerated) and instantly recognizable than Leonardo da Vinci. But to think of Leonardo as an old master—with all its connotations of being staid, traditional, somehow old-fashioned, and boring—is to do this extraordinary man a grave injustice. There is nothing stale or predictable about a man whose personal foibles irritated and frustrated contemporaries as much as his brilliance and creativity dazzled and awed them. One thing is for sure: Whatever Leonardo was, old and boring he was not.