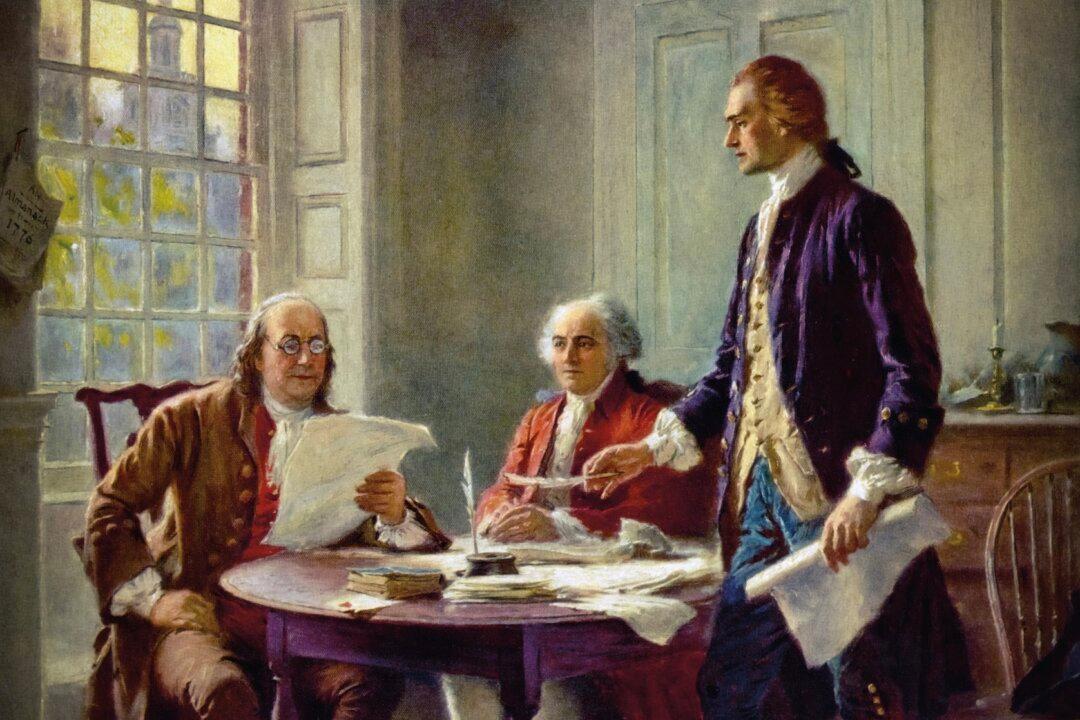

While we know a great deal about early Protestant contributions to America’s founding, we hear less about the very early Jewish settlers.

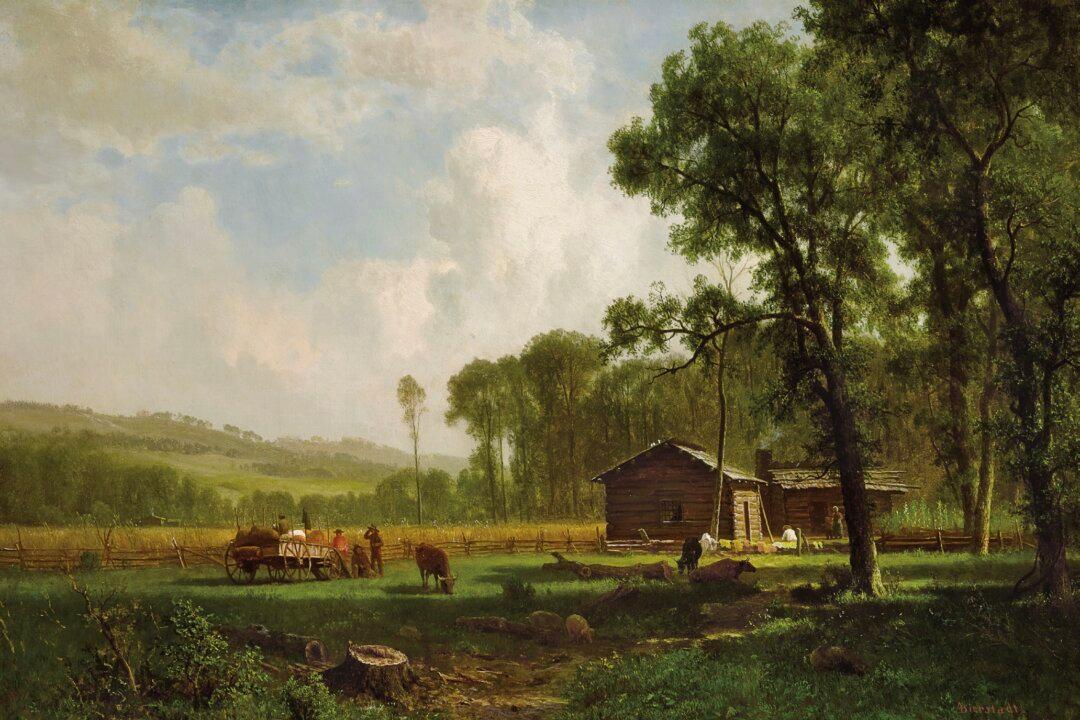

Mordecai Sheftall was born in Georgia when it was one of America’s newest colonies. His parents were Jewish immigrants from England, with skills but without funds. In 1733, a British member of Parliament arranged for 40 families to get a fresh start in a new environment an ocean away. Tailors, bakers, carpenters, merchants, and farmers were among the debt-ridden who were chosen.