In anticipation of the second annual Chinese International Figure Painting Competition, The Epoch Times will visit the achievements of past masters, especially those of the Renaissance.

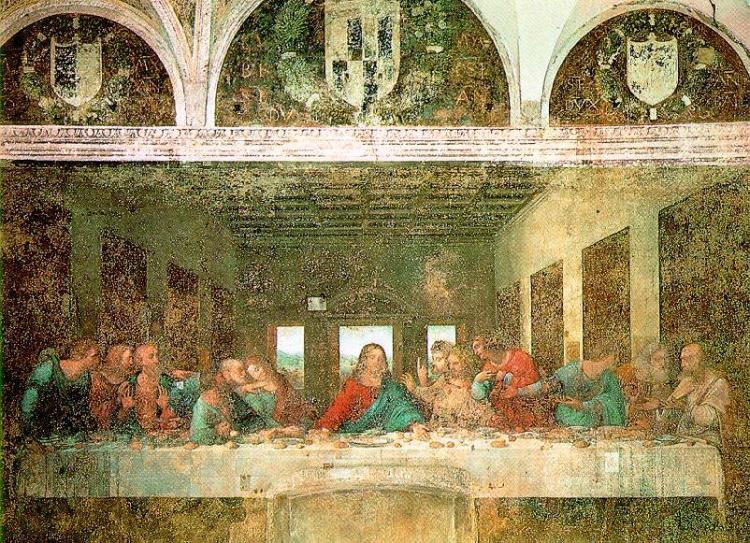

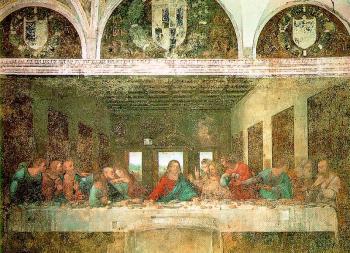

Leonardo’s Last Supper Raises the Bar

The titans of the Renaissance—Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael—are closely knitted together with threads of style, complexity, and a return to classic culture.

HIGHER STANDARD: Leonardo's fresco on the refectory wall of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, perfects the theme of Jesus' Last Supper with his disciples. artrenewal.org

|Updated: