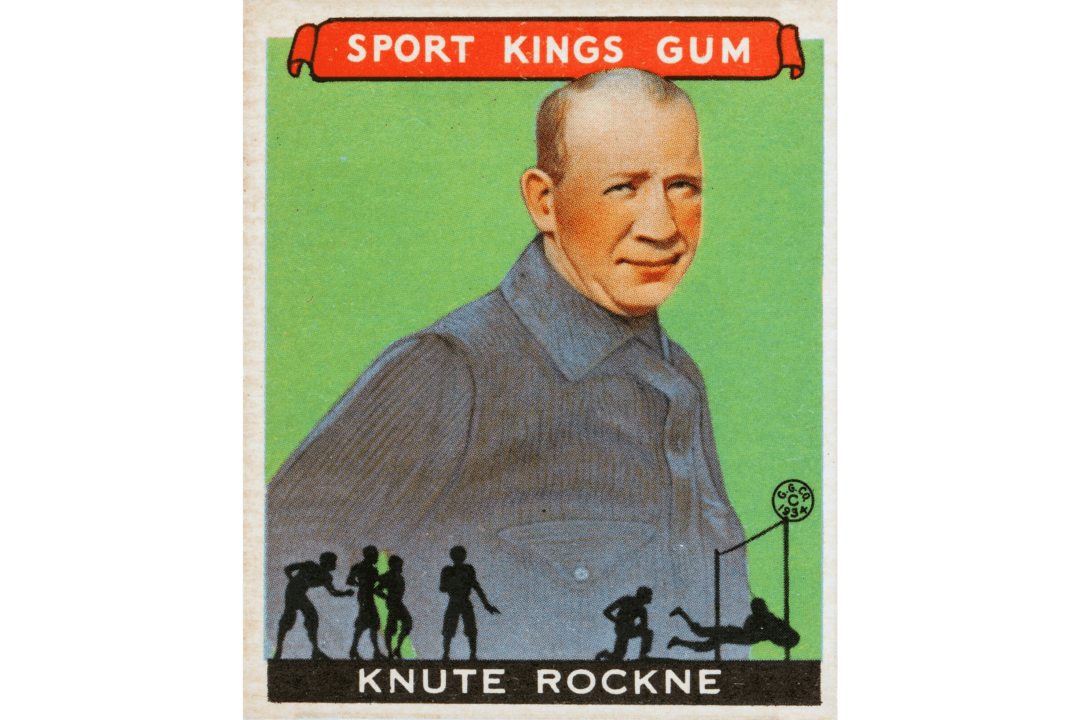

Knute Rockne was 5 years old when he arrived in America with his mother and sisters from Scandinavia. By the time a plane crash claimed his life at age 43, he was a national hero, “the dominant personality of American sportdom.” He developed and coached the “Fighting Irish” of Notre Dame into a sporting marvel.

Indeed, Rockne elevated the stature of college football, ushering in an era of prestige previously unknowable. Quotable, affable, and eminently successful, his 88 winning percentage set the highest standard in major college football history.