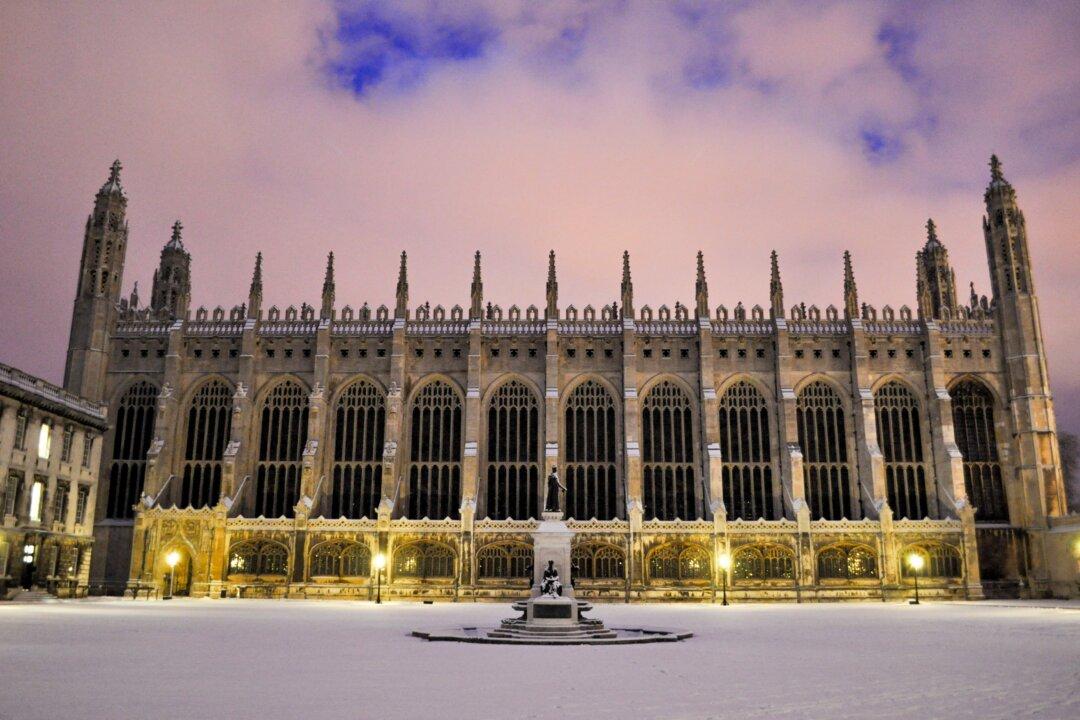

The central point and showpiece of the centuries-old Cambridge University campus is its chapel. King’s College Chapel, planned by Henry VI in 1515, is a colossal, freestanding stone structure conveying the Gothic style of the medieval age. Gothic architecture, which emerged from Romanesque architecture, is distinguished by its distinctly pointed arches, as opposed to the rounded arches of its Romanesque predecessor. Gothic architecture is also ecclesiastical in nature, meaning it suited the goal of churches to architecturally reach upward with extraordinarily tall rooftops, spires, and pinnacles.

King’s College Chapel is a regular house of worship for the students at Cambridge University and the residents of Cambridge, England. People today enter regularly and marvel at the exceptional architecture and craftsmanship in stone, wood, and glasswork achieved centuries ago.