After spending more than five years in Paris, Julia Child went to the south of France in 1953, where her husband, Paul, was assigned duty as a cultural officer at the sleepy American consulate in Marseille. The port city was a “labyrinth,” a city of “hot noise,” Child reflected years later. A short, hard-to-endure interval at a hotel yielded to their taking an apartment in the Old Port area. “I was so relieved to have a kitchen, albeit one the size of a sailboat’s galley, that I whipped up a wizard soupe de poisson [strained fish soup] for lunch on our first day in residence.”

Child and her co-authors were already deep into their cookbook, a work designed to make French cuisine accessible (living in Marseille would increase her culinary range with soups and fish). The book’s “ideal reader [was] the servantless American cook who enjoyed producing something wonderful to eat,” she stated in “My Life in France,” a memoir written with her grand-nephew Alex Prud’homme. She considered the meticulously developed recipes to be her intellectual property and was upset when an editor shared one from the work-in-progress, leading to her taking countermeasures by writing “Eyes Alone” and “Top Secret” when sending out future sections for evaluation. This glimpse of hard-nosed Julia should come as no surprise. After all, during World War II, she handled espionage materials while serving in the U.S. Office of Strategic Services.

Although Child died in 2004 at the age of 91, her legend endures and even grows. For example, her TV kitchen and copper pans are on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. And besides being the subject of biographies and memoirs, the gourmand has proven a compelling cinematic subject. Meryl Streep’s Oscar-nominated portrayal in “Julie and Julia” is indelible. The 2009 film is based on Julie Powell’s account of cooking 524 of Child’s recipes in a small New York apartment. Co-star Amy Adams’ portrayal of Powell is capped by a scene in which she visits Child’s kitchen at the museum and, in touching tribute, leaves a stick of butter.

Before Thanksgiving of 2021, the documentary “Julia” was released, with co-directors Julie Cohen and Betsy West giving a straightforward account of Child’s life. When the filmmakers first considered the story, they asked, “Well, why is it that in the ’70s and ’80s, people really started cooking?” It was largely Child’s influence, West told the Los Angeles Times. “She sparked something that so changed the culture.” Filming has begun for the forthcoming HBO Max series, also titled “Julia,” which stars Sarah Lancashire in the eponymous role.

“Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” Child’s 1961 landmark work written with Louisette Bertholle and Simone Beck, spent years atop bestseller lists. Until then, Americans had regarded fresh fish and produce with suspicion; supermarket aisles of the era were loaded with canned fruits and vegetables, powdered drink mixes, and frozen dinners. The savors of herbs were little known; part of Child’s lesson was about shopping for yourself and choosing the best ingredients.

The recent documentary goes to lengths to illustrate how different Child was from other women on television when “The French Chef” debuted two years after the book’s publication. Paul and Julia had settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Boston’s public television affiliate WGBH filmed her maneuvers in extended takes, resulting in the opportunity to improvise not only with the cooking—she advised the viewer never to apologize for mistakes—but also with her ad-libs. Of course, we crave the nuances of Child’s recipe for an authentic bouillabaisse or her best technique for slicing up a chicken, but she couldn’t have facilitated the transition from master chef to celebrity chef without her singular verbal ability. (“The French Chef” now streams on the service Pluto TV.)

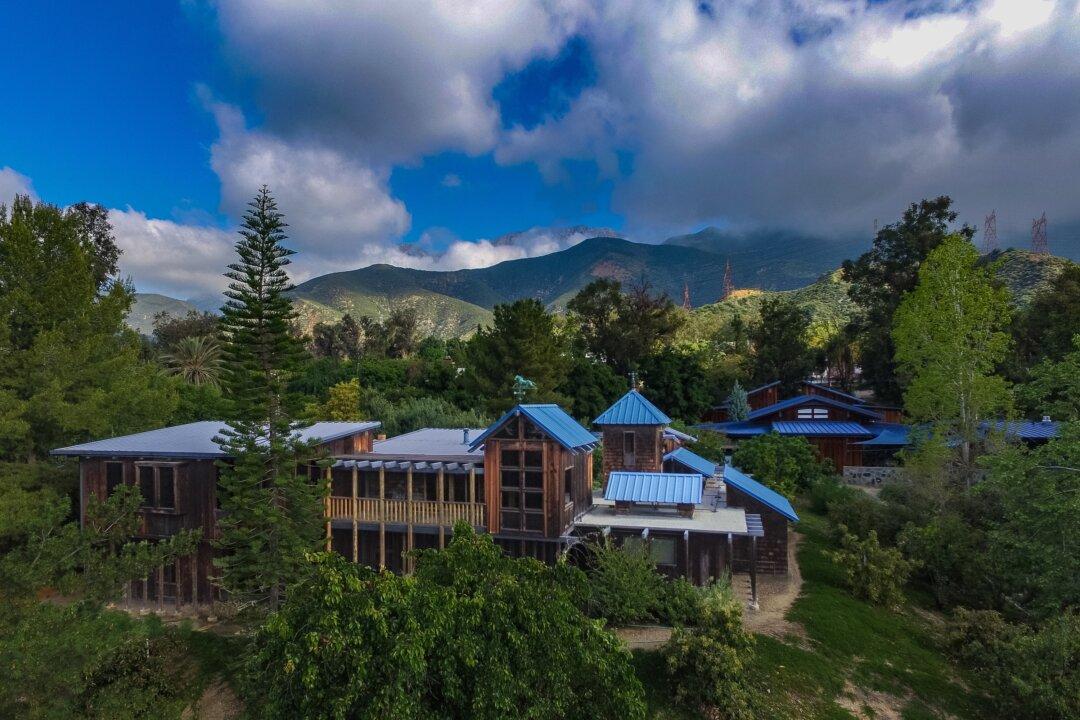

Growing up in Pasadena, California, Julia McWilliams wanted to be a writer, and her private school education and history degree from Smith College left her well-equipped even if, as she is quoted in the documentary as saying, she was “a butterfly.” She went on to prove herself formidable, blunt, and of a sound critical intelligence. She managed to score with naturalness. As to the reason, “My Life in France” offers a clue—namely, her way with words. Becoming fluent in French, she prowled the marketplace’s inner stalls and listened to every fishwife’s formula for a hearty soup stock. Even at the end of the Childs’ diplomatic career, when Paul was posted to Oslo, she learned enough Norwegian to read the newspaper and handle the shopping.

On the one hand, Julia Child could adopt a professorial tone. An example is found in this assertion: “I devoted myself to piscatory research, as we tried to systematize the nomenclature and cookability of French-English-American fish for our readers.” On the other hand, she sprinkles in obscure but whimsical words like “collywobbles” for “bellyache,” delivers contemporary slang like “dullsville,” and drops fanciful nouns like “balderdash,” “nincompoop” and “the Real McCoy.” Additionally, she displayed a knack for alliteration and poetic free association, as in the account of a trip from Nice: “We drove back to Marseille through the arrière-pays [hinterland] of scraggle-topped crags—their tops powder-sugared with snow—and forests of pine and cork oak.” Besides Emmy and Peabody plaudits for her cooking show, she also won a National Book Award in 1980, for her cookbook “Julia Child and More Company.”

Still, for all of her sophistication and accomplishments, Child was the prankster who, in the early 1920s, had whizzed around Pasadena on her bike. She smoked her father’s cigarettes and cigars, threw mud-balls at cars, and dropped rocks from an overpass onto passing trains. Once, while prowling around a house construction site with a friend, she got stuck in the chimney.

She had started out conventional enough, and that would account for her desire, upon returning to America from France in 1954, to eat “an honest-to-goodness American steak!” she recounted in “My Life in France.” Unfussy and unassuming, Child always had something of the Stars and Stripes about her even when she recalled “the pleasures of the table, and of life” in her memoir, before signing off, “Toujours bon appétit!”

This article was originally published in American Essence magazine.