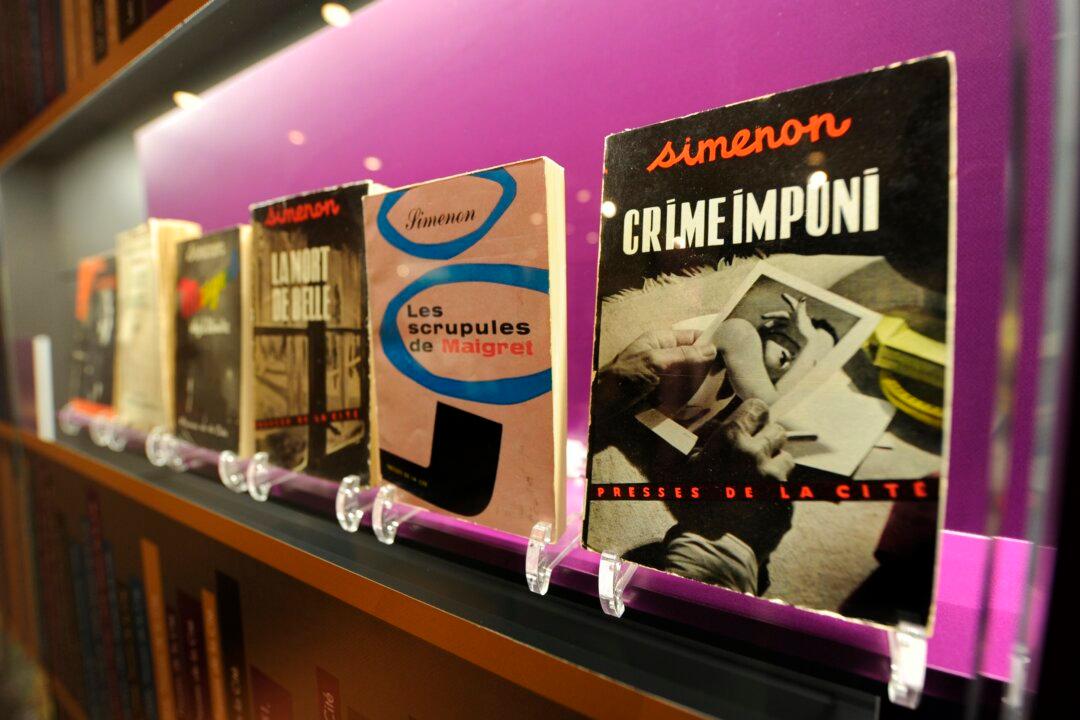

French publisher Librairie Arthème Fayard introduced the world to Jules Maigret, an inspector with Paris’s Brigade Criminelle, with the 1931 novel “The Strange Case of Peter the Lett” (since republished as “Pietr the Latvian”). A slim, fast-paced police procedural, the novel helped to redefine crime and detective fiction in France less than a decade before the collapse of the Third Republic (1870–1940).

In 1931, there were two primary archetypes of the fictional detective: the ratiocination machine and grand puzzler-solver first created by American Edgar Allan Poe and perfected by the British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and the so-called hard-boiled private eye of the pulp magazines and pens of authors Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.