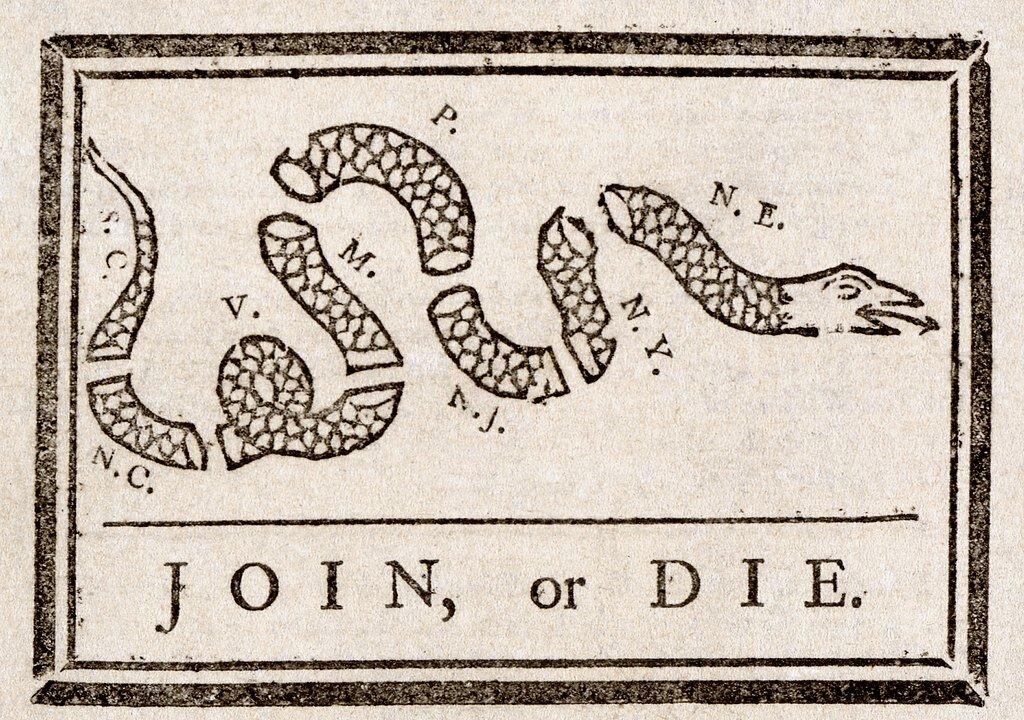

Benjamin Franklin published “Join, or Die”—now considered to be the most famous colonial political cartoon—on May 9, 1754. It appeared in “The Disunited State,” an editorial in his Pennsylvania Gazette, which was the most successful newspaper in the colonies at that time. The symbolism of the cartoon’s fragmented snake is significant, and the message is simple: If we do not unite, we shall die at the hands of our nemesis. It was such a powerful message that it was used again during the American Revolution, and in other wars and crises that were to come later in America.

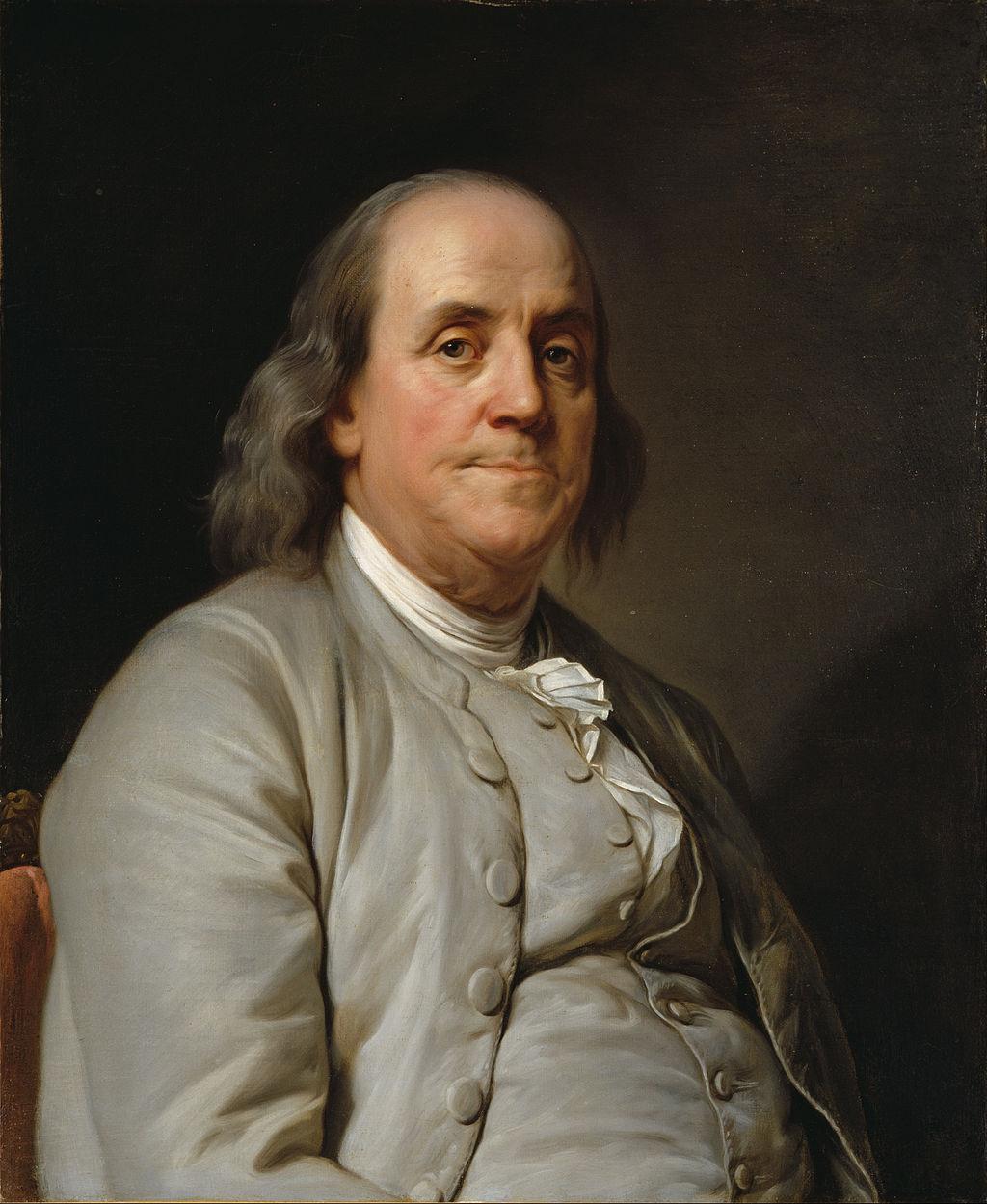

"Benjamin Franklin," circa 1785, by Joseph Siffrein Duplessis. Public Domain