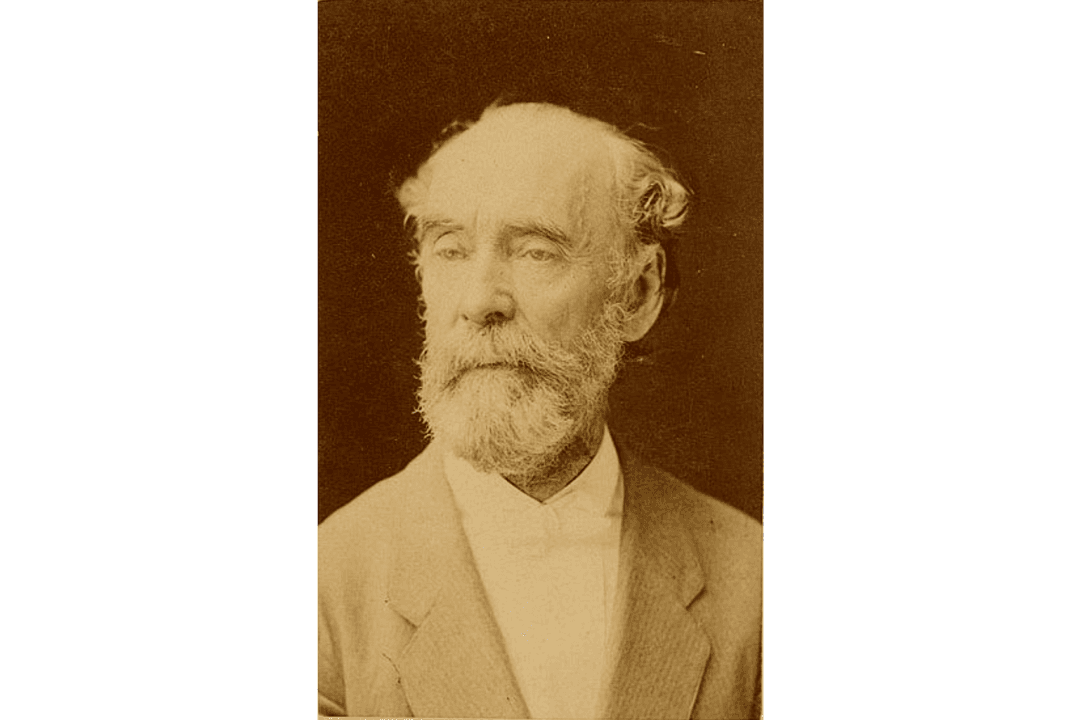

Fifteen years before John Wise (1808–79) was born, Americans witnessed the country’s first flight. President George Washington was even on hand to watch as French aeronaut Jean Pierre Blanchard soared in his balloon above and away from a Philadelphia crowd. Wise was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a city west of Philadelphia. He grew up reading about the adventures of European balloonists, and though he apprenticed as a cabinetmaker and then became a piano builder, his head was always in the clouds.

One day, as a young boy, he climbed to the top of the local church with his pet cat. He had created his own parachute, and from the steeple of the church, he released his cat, watching as it slowly, and thankfully safely, floated to the ground. In 1822, he attempted something that appeared a little safer, but with adverse results. He created a small fire balloon, called a Montgolfier, which is powered by fire, typically a candle, placed inside of it. Although there was no cat attached, the Montgolfier struck the roof of a house, which caught on fire.