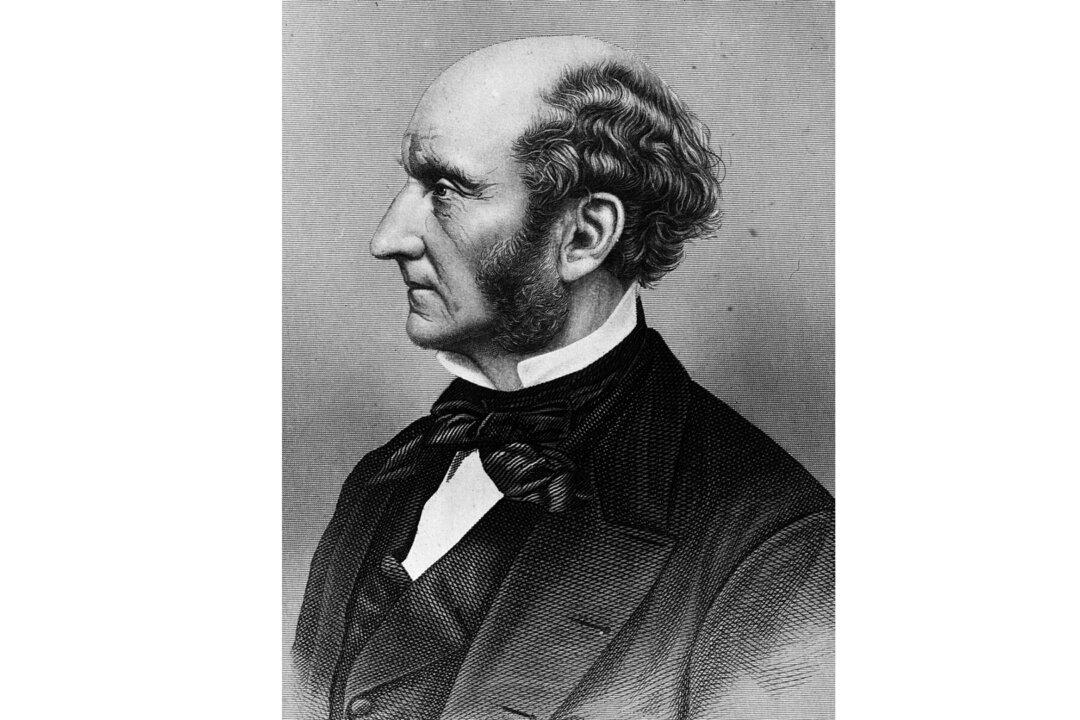

In his influential 1859 essay “On Liberty,” philosopher John Stuart Mill articulated one of the most compelling defenses of freedom of speech ever written. The book became so popular after its publication that British undergraduates in the 1860s were thought to know it by heart. Historian Peter Marshall described Mill’s work as “one of the great classics of libertarian thought” for its emphasis on individual freedoms.

Today, it’s the symbol of office for the president of England’s Liberal Democrat Party and serves as an emblem of democratic societies around the world. As the American electorate prepares for the 2024 presidential election, Mill’s comments can illuminate the value of the democratic process and the importance of open debate.