Not many female literary protagonists come to mind as likely to inspire university debates over their merit as heroines. Fanny Price, the heroine of Jane Austen’s “Mansfield Park,” seems the least likely candidate to inspire controversy. Yet during my time in college, I attended a debate between two English professors regarding Fanny Price. At the end, students were asked to vote on whether or not Fanny was a worthy heroine. The room was pretty evenly divided, with Fanny just barely squeaking out a victory.

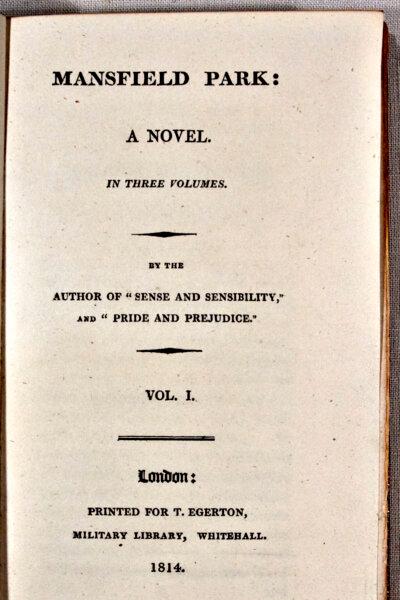

Title page of “Mansfield Park,” 1814, by Jane Austen. Indiana University. Public Domain