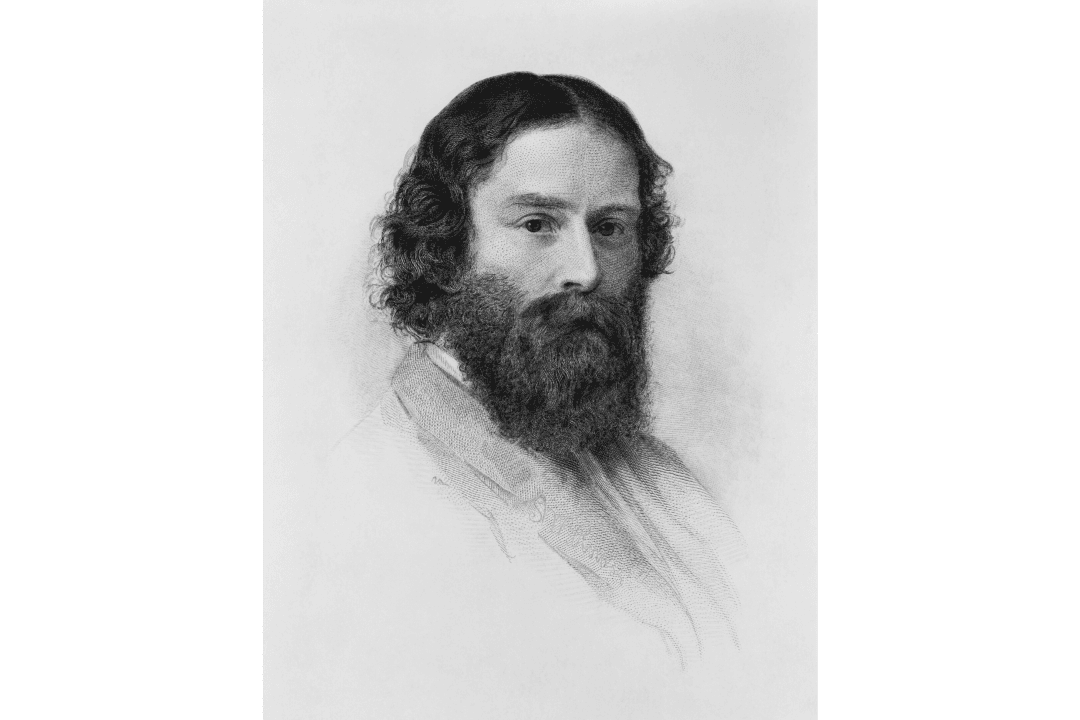

At a young age, James Russell Lowell (1819–1891) could have chosen multiple career paths, but he decided to follow his passion for the written word he had acquired in his youth. His unique flair for using humanity and nature in his poetry helped him become one of the most famous “fireside poets” of the 19th century. He wrote simply, and families recited his poems as they gathered around the hearth. Through his work, Lowell became one of the most influential poets and abolitionists of his time.

Lowell was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1819 to a Unitarian minister. He attended Harvard at 15, but he was a horrible student who often skipped class and got into trouble. While attending college, he became class poet. Later, he was admitted to the bar after taking just a single law class.