A whopping two-thirds of human conversation is gossip about others—a rate that holds true, anthropologists say, for radically different cultures around the world. Something like 90 percent of that gossip is negative.

What makes this mode of communication so irresistible? In her new book, Is Shame Necessary? New Uses for an Old Tool (Pantheon, 2015), Jennifer Jacquet notes that gossip is a subcategory of shaming, one of the oldest and most universal methods used to punish those who violate social norms—and, in turn, make those who obey them feel a stronger connection to the group.

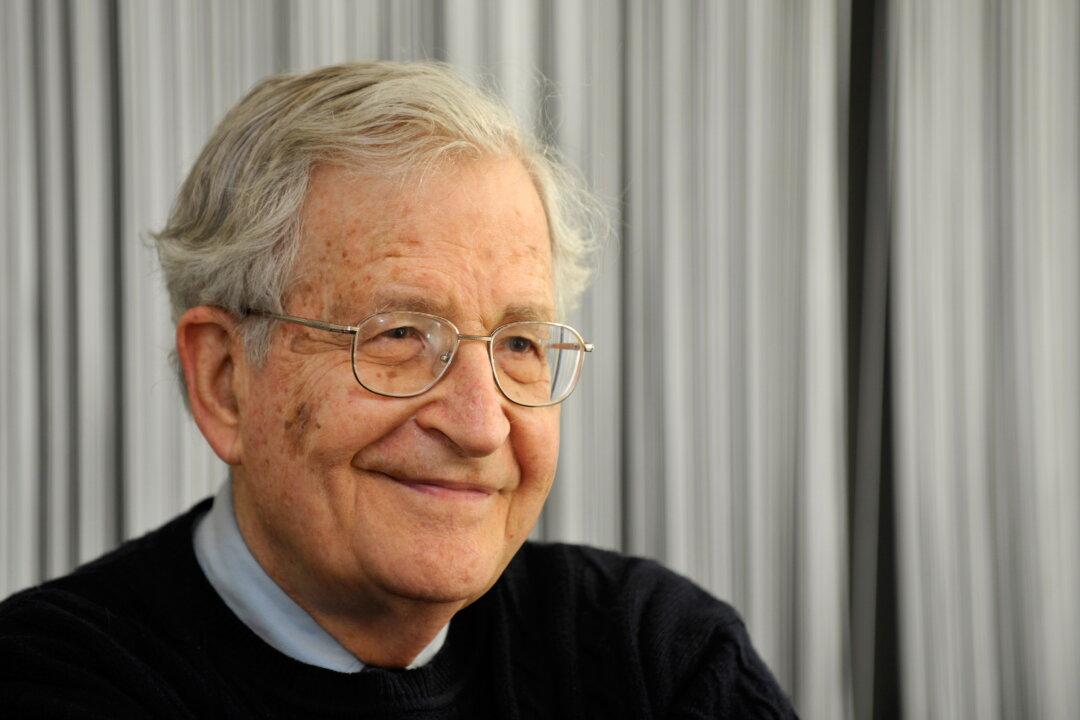

While it may make us cringe to see shame being used by the strong against the weak, Jacquet, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University, sees merit in reversing the formula. She lays out a roadmap for how small groups of concerned citizens could use shame to change the behavior of big corporations and even governments—and offers a provocative argument for why, particularly in the realm of environmental activism, shame may be a more useful emotion than guilt.

Traditionally, shame works by exposing—or threatening to expose—the transgressor to an audience, and it’s likely something our ancestors experienced much the same way we do today.

Our responses—slumped shoulders, caved chests, blushing, and an impulse to cover the face—don’t vary much across societies, but the cause is shaped by the culture.

You'd feel ashamed if your date neglected to tip at a restaurant here in the US, Jacquet points out, but not over the same situation in France. And among the Bakairi Indians in Central Brazil, eating in public is shameful, while going about nude is not.

Inescapable shame (for however long it lasts) is a feeling many of us associate with the worst moments from our teens, or with stories from a crueler past—think of poor Hester Prynne and her scarlet “A” for adultery. But that doesn’t mean it’s behind us.

As recently as 2012, Jacquet writes, “a woman who had been caught driving on the sidewalk to go around a morning school bus full of children was sentenced to standing for two hours on the sidewalk with a sign that read: ONLY AN IDIOT WOULD DRIVE ON THE SIDEWALK TO AVOID A SCHOOL BUS.”

And although some forms of shaming—especially ones that alter the physical body, like branding debtors with hot irons—have fallen out of fashion, others have found fuel in 21st-century technology.

But used sparingly and conscientiously, Jacquet argues, shame could be used to get the attention of some big-time “bad apples” causing headaches for the rest of us—especially when it comes to major collective action problems like climate change. It’s just a matter of being creative and focused about choosing our targets.

NYU writer Eileen Reynolds checked in with Jacquet to ponder guilt, shame, and what the two feelings have to do with what you eat—and, of course, tweet.

What’s the difference between guilt and shame?

Guilt is often defined as an internal conversation between you and your own conscience, whereas shame is the threat of social exposure—it affects your interpersonal relationships. What’s really interesting, though, is that some cultures don’t even have a word for guilt. Why is that? I speculate that these are cultures in which you don’t spend very much time alone—and without that, it’s hard to distinguish between your own internal conscience and the broader sentiments of the group.

Even in the West, guilt seems to be a relatively new phenomenon. Shakespeare, for example, uses the word “guilt” 33 times, compared to “shame,” which appears 344 times.

Companies like Google or SeaWorld don’t experience guilt, but it’s much easier to argue that they do in some sense experience shame—because they change their behavior in the face of public disapproval, and they defend their reputation.

You’re pretty tough on the green consumerism movement, which you view as a guilt-assuaging distraction from true activism. but if everybody were an environmentally conscious shopper, wouldn’t companies that ignored those values go out of business?

This is intuitively tough, because you want to say, yes, should everybody out there want organic food, maybe every company would voluntarily switch to organics. They would all charge more, and we would all be getting what we want. That’s an okay thought experiment. The problem is that everyone’s voluntary participation is very unlikely to happen, given the evidence out there and the historical patterns of social concern.

Conscientious consumption remains a minority exercise—it’s not demanding blanket social change or the really high threshold of participation you'd really need to address this collective action problem.

Think about something like immunization—you need something like 90 percent of people getting vaccines for there to be true immunity, and as soon as you make it easy for people to opt out, you get down to 86 percent compliance and it doesn’t work anymore. That’s why you end up needing regulation to reach that threshold, to make sure everyone is safe.

What are some examples of how weak-against-the-strong shaming has worked for environmental activism?

Take the case of Blackfish, [the documentary about orca whales in captivity]. Since that film came out, SeaWorld has lost 60 percent of its stock value, revenues have decreased 7 percent, attendance has decreased 5 percent, and they’re in the midst of a public relations nightmare that wasn’t caused by a lawsuit or by government intervention. Instead, a few really concerned filmmakers and small but outraged and highly engaged audience have had a tremendous impact on SeaWorld’s reputation.

Another example is the Rainforest Action Network’s shaming campaign against banks that are financing coal companies doing mountaintop removal in Appalachia. After a five-year campaign, two of the nine banks have changed their policy to prevent the funding of coal companies.

I’m not saying that this two out of nine is a major success, or even sufficient—hopefully someday this will be illegal. But it shows that shaming can act as a stop-gap for the period between when people are outraged about something and when there’s actual legislation passed to stop it.

What methods do companies use to fight back against shaming campaigns?

One thing that banks do is shift responsibility to smaller firms that don’t have the same reputation as the big firm. And there are principles of limited liability built into the legal system, so in that way the cards are stacked against citizens in terms of making corporate change.

It’s also true that publicly traded corporations tend to be more responsive to negative reputation than privately held ones. Compare BP, whose stock value took a huge dive during the oil spill and is now working hard on reputation cleanup, to Koch Industries, which is privately owned and therefore seems more insulated from public disapproval.

There’s also psychological research on how we hold individuals more responsible than we do groups, which allows groups to behave worse than individuals can. And, of course, the other thing that corporations do is wait it out—just let it blow over.

Can the shaming approach backfire?

Yes, and in such interesting ways! Sometimes it ends up changing the norm in a direction completely opposite the one you were hoping for. This seems to happen to the Westboro Baptist Church all the time. When they went to Silverton, Oregon to protest the first openly transgender mayor, they held huge signs that said “shame.”

But then a lot of members of the community turned out in protest—men turned out in women’s clothes and made such a counter-display that the town solidified around this transgender mayor more than it would have if the Westboro Baptist Church activists had never visited.

Before, a lot of the members of the community, from what I could find, thought the mayor was a good politician but weren’t so keen on him being transgender. But afterward, the message was “actually, this is a badge of honor—having a transgender mayor makes us special.” That’s how you know your shaming campaign failed—when you actually made that norm more solid than it was before you tried to expose it. That does show the danger of the tool—it’s not a predictable outcome.

How has the internet changed how shaming works?

For most of history, punishment was somewhat costly for the punisher. The online environment has reduced that cost so much, because so many of the punishers—the shamers—are anonymous. They’re not experiencing the reputational impact of their behavior, and some of them are so harsh that none of us would tolerate them in real life.

Someone asked me the other day whether the internet isn’t just the new town square, the new village stocks. I think the difference is that even though the punishers would wear hoods or masks in the town square, everyone still somewhat knew who they were. The identities of online punishers are much more ephemeral.

There’s also the fact that social media moves so quickly. Knee-jerk comments have always gotten people in trouble, but now those are permanent—and searchable. All of those things do, I think, amplify shaming.

Can that amplification effect also be used by the weak against the strong?

Twitter is a tool like anything else. Because of its searchability, corporations are monitoring it closely—that’s free and easy and you can do it from your desk. That means that the Susan G. Komen Foundation was very easily able to monitor the volume of negative tweets after they removed funding for Planned Parenthood, and they could then analyze the content of that chatter.

What matters a lot to corporations is the volume of negative chatter. This is the kind of cool part of social media—if you can get a lot of eyeballs on a problem or a corporation really quickly, it can have a big impact.

Source: NYU. Republished from Futurity.org under Creative Commons License 4.0.