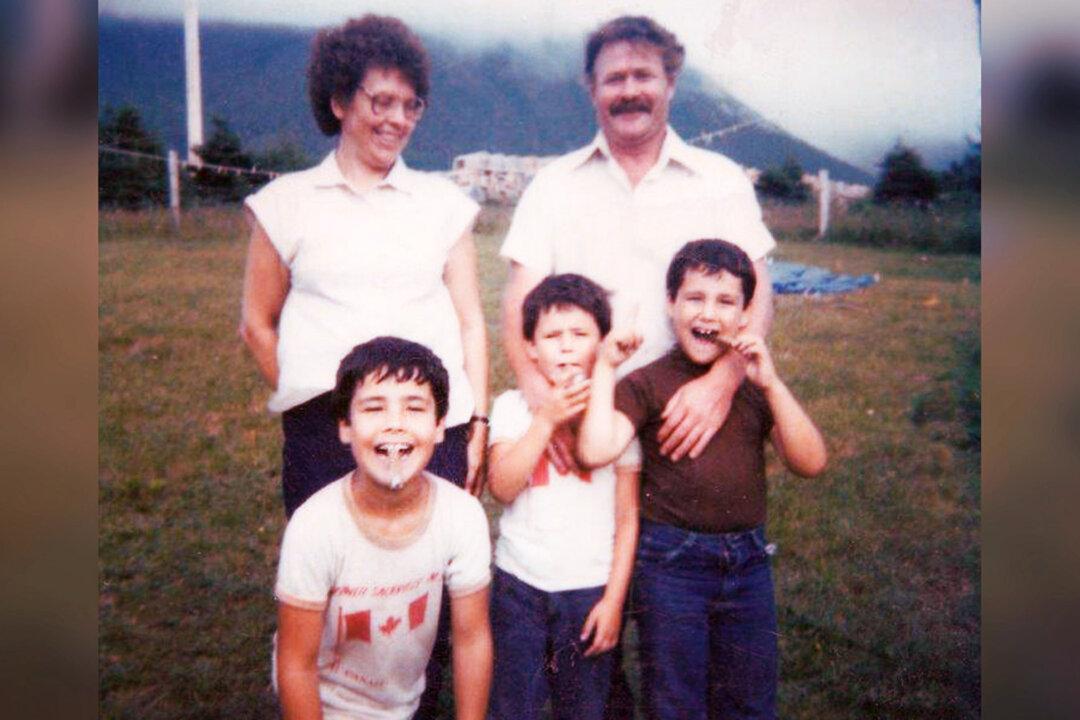

Jesse Thistle of Toronto is a published author and expert on the indigenous cultures of Canada. But not so long ago, he was a “street guy” with nowhere to stay, addicted to drugs, and stealing coins out of wishing fountains just to get by.

After time spent in jail and rehabilitation, and at the dying wish of his grandmother, Jesse decided to turn his life around. He is now a university professor and Ph.D. candidate, his life unrecognizable from the one he once led.