TEL AVIV—“Without feeling the light in nature, it is not possible to make a good picture,” photographer Leonid Padrul said when I met him in his studio at the Eretz Israel Museum. I had just seen his landscape photographs and the catalogue pictures he took for the museum.

Padrul searches and finds gold. “You not only need to know how to photograph, you also need to feel in your depth how to show the life of the object,” he said.

“It is by chance that what I do and my profession are the same,” Padrul said. He started to photograph in his youth, in the Ukraine, his birth country. He was a sportsman, a cyclist, and a swimmer.

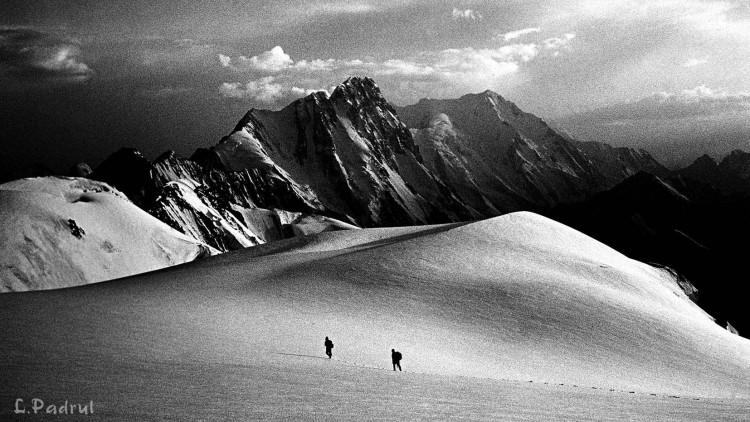

In the Mountains

After the military service, he joined a journey to the high mountains of Tien Shan, situated between China and Kyrgyzstan. “It was not a voyage; it was a cartography expedition and everything was planned,” he added.

In spite of the mission’s difficulties, Padrul knew what he was looking for and began a personal documentation. “From time to time, I told the friend to whom I was tied with a rope to stop in order to get the best frame there was,” he said.

“One day I saw for the first time in my life something wonderful—I was standing above a cloud,” he said. “Whenever I saw something interesting that an ordinary person wouldn’t know, I photographed it.”

The physical tests turned out to be a journey toward “the good picture” for Padrul. After walking for hours, he would suddenly see something special. He said that hardships helped him “feel the landscape and connect to nature.” “Facing such huge nature, a person can only find himself inside of it.”