Don McCullin knows the people he photographs. His subjects are not the “unfortunate.” They are not anonymous “collateral damage,” nor the scattered debris of globalized bombardments. The subjects of McCullin’s photographs are living people whose misfortune it has been to live in hard times.

“Don McCullin: A Retrospective” at the National Gallery of Canada displays 134 photographs the photographer made over more than 50 years, 1958–2011, on assignment throughout the world.

The black-and-white prints bear witness to the humanity McCullin sees in the people he photographs. We who are usually far away from these conflicts are skilled in setting aside the uncomfortable images of international news reportage.

The National Gallery’s installation of McCullin’s photographs, however, sets a trap for the would-be disaffected viewer.

Walking into the first room of the Don McCullin retrospective, one of the first photographs the visitor sees is a picture of sheep. In McCullin’s early morning photograph, a herd of sheep are approaching us on a nearly empty road in a grim, grey industrial sector of town. One man, visible in the distance, appears to be dressed for the office.

Had we been there that morning, we would have stepped to the side of the road to let the sheep go by. McCullin, however, stepped out in front of the herd to make this photograph in 1965. His point-of-view is now ours. The photographer’s title on the gallery’s small label to the side of the black-and-white print tells us the sheep are walking down Caledonian Road, London, to the slaughter house.

Slaughter, waste, and loss are subtexts throughout the National Gallery’s retrospective exhibition of McCullin’s work. The imagery of the photographs is the storyline. The viewer has good reason to look again and again.

Homeless Irishman

In the first room, two photographs are labelled “Homeless Irishman, Aldgate, East End, London, 1970.” One shows us a man sleeping rough on the street, a figure curled into the gutter amid the trash. Another is a full-face portrait of a working man, perhaps 40 years old. He is alert, watchful, intelligent, with a paint-spattered face. The second photograph prompts the viewer to look more closely at the first. The “homeless Irishman” of both photographs is the same individual. Whatever work he gets is not enough for his needs.

McCullin’s photographs are often images of compassion and loss. In 1968, McCullin accompanied the United States 5th Marine Regiment into battle at the time of the Tet offensive in Vietnam. Two portraits from this time bear witness to the cost of survival. In one, a young American Marine, looks at us and through us, his nerves tensed for the next round of shellburst.

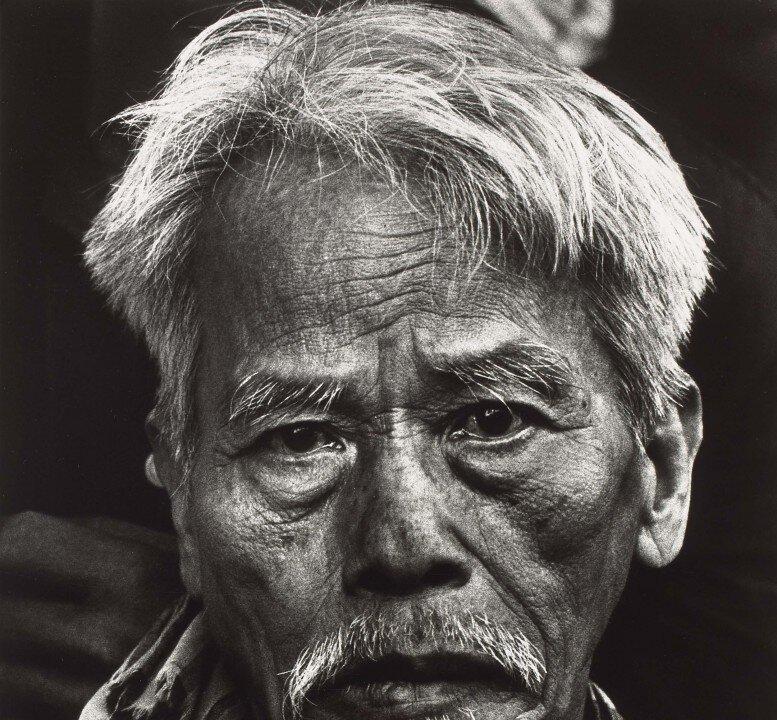

The second portrait is that of a very old Vietnamese man. His face is one of bone-weary sorrow. The old man and the marine are brothers-in-spirit to the homeless Irishman.

The places McCullin has photographed include hard-scrabble, post-war Britain, Beirut, the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, Londonderry, Zambia, Biafra, Cyprus, Vietnam, Berlin, East Pakistan, and many others. There have been so many wars, and so many displaced, dispossessed, cast-aside peoples throughout the last century.

Quiet, Harmonious Scenes

The last room of the Don McCullin retrospective at the National Gallery, however, is organized differently.

The photographs displayed here appear to be quiet, harmonious silent scenes. They include compositions of apples from a garden on a table, a solitary, still camel in Sudan, one elephant in India, an empty road in a field, a snowstorm, and so forth. The labels on the photographs, however, may remind some viewers of the older histories of these lands.

The road McCullin photographed, for example, winds though the WWI battlefield of the Somme. During the Moghul years, both the elephant and camel were effective war machines. The snowstorm is one he saw while climbing Hadrian’s Wall, a fortification built almost two thousand years ago during the Roman conquest of Britain. Apples from a garden in one old story led to one brother murdering another.

On the final wall of the exhibition, the exhibition designer has posted a statement of purpose from McCullin. Dated 1994, we read: “Photography for me is not looking, it’s feeling. If you can’t feel what you’re looking at, then you’re never going to get others to feel anything when they look at your pictures.”

Most of the photographs in the Don McCullin retrospective are gelatin silver prints, one is an ink-jet print, and 21 are platinum prints. The galleries are well-lit and the signage for each of the photographs is complete. A hard cover catalogue accompanying the exhibition is priced at $25.00.

Maureen Korp is an independent scholar, curator, and writer who lives in Ottawa. Author of many publications, she has lectured in Asia, Europe, and North America on the histories of art and religions. [email protected]

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 20 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.