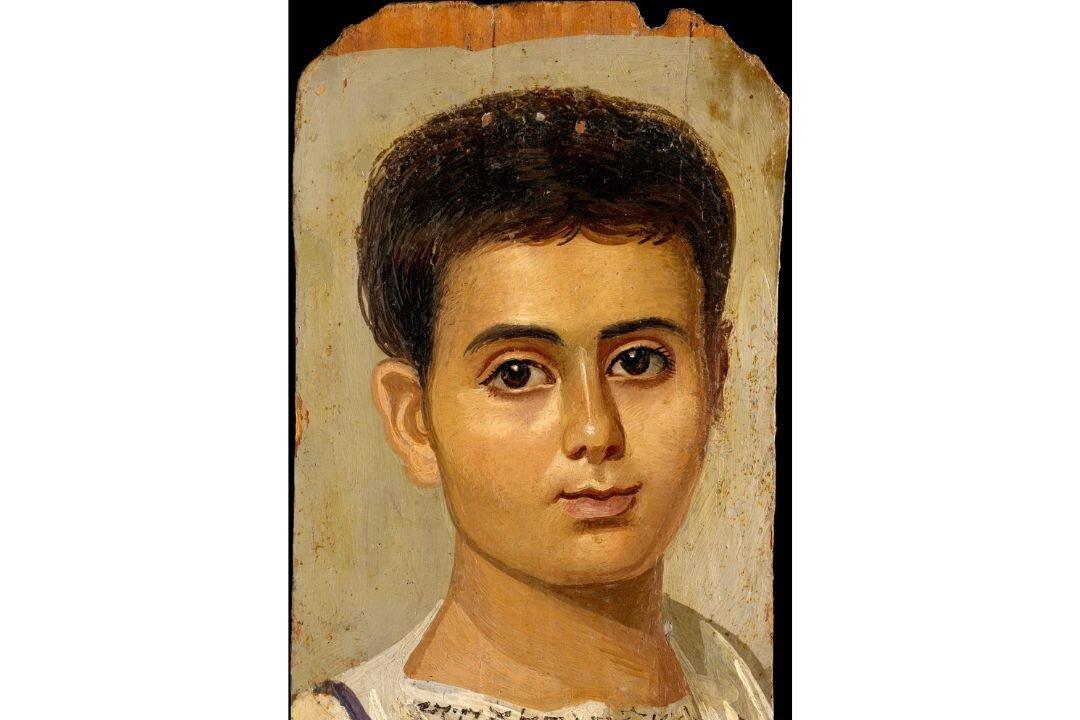

Perhaps more than any other art genre, portrait and figurative arts appeal to our shared humanity. Each face that peers out of a portrait shares emotions and facial expressions familiar to us all—in a stranger’s portrait, we can see ourselves.

A small selection of ancient paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) in New York City shows the enduring nature of portraits painted true to life. From afar, some of the fresh faces peering from the portraits look like recent renderings in oil. Yet ancient Egyptian artists painted these portraits more than 1,900 years ago by using encaustic paint, a mixture of beeswax and pigments. With encaustic paint, they achieved fluid, luminous paintings similar to those that 15th-century oil painters created centuries later. Up close, we can see beeswax grooves on the portrait’s surface.