Austrian painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller held nature in high esteem. “Nature must be the only source and sum total of our study; there alone can be found the eternal truth and beauty, the expression of which must be the artist’s highest aim in every branch of the plastic arts,” he wrote in 1846.

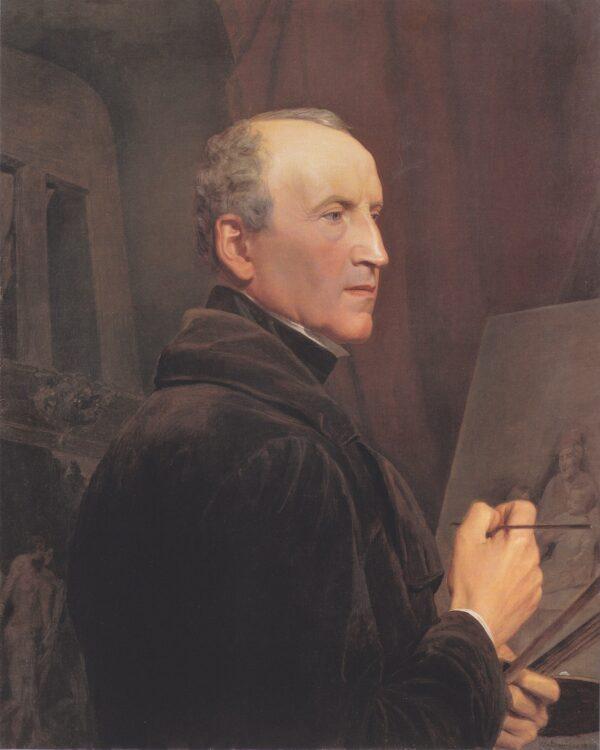

"Self-Portrait at the Easel," 1848, by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller. Oil on canvas; 69 1/2 inches by 56 1/2 inches. Public Domain