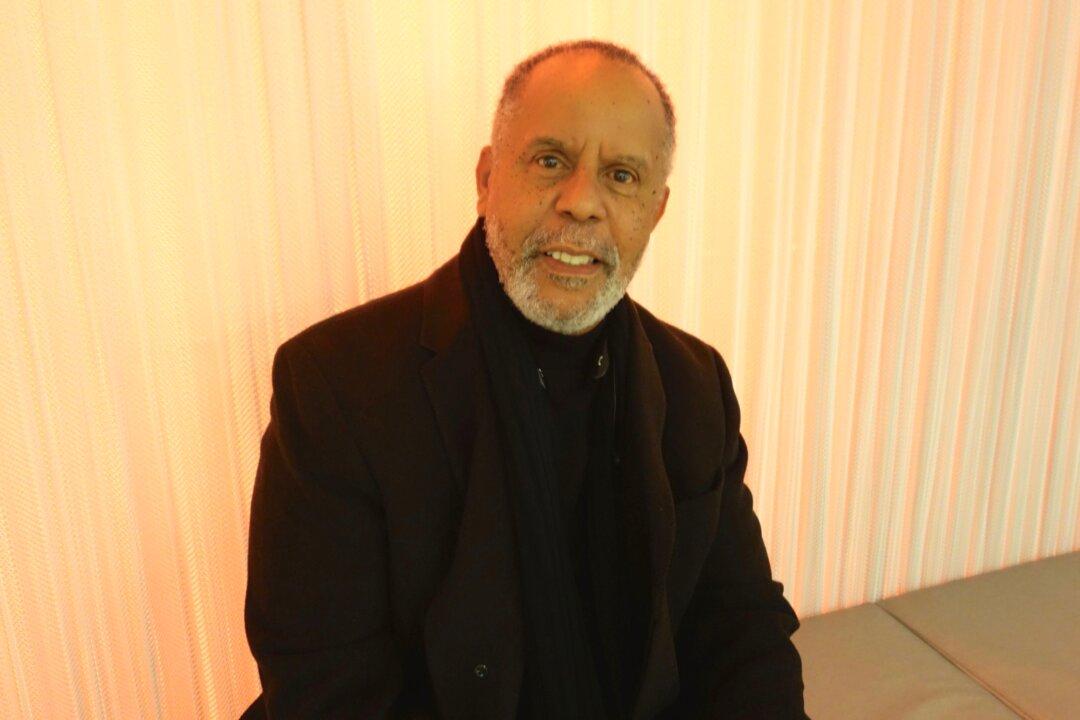

ATLANTA—”I always had my sketch pad in my gas mask,” said Ashley Bryan. He was chatting with Dr. Collette Hopkins of the National Black Arts Festival. Mr. Bryan was being honored at the Auburn Avenue Research Library. The Atlanta literary festival named for him just celebrated its fourth year. His road to honors was long.

Ashley Bryan drew all the time and studied so well that he finished high school in Harlem at sixteen. College officials told him it would be wasteful to give a scholarship to a colored student. His teachers asked him to apply to Cooper Union—a blind test. “You put your work in a tray, sculpture, drawing, painting, and it was judged. They never saw you. If you met the requirements, tuition was free, and it still is to this day,” said Mr. Bryan.

World War II interrupted his education. He was drafted out of Cooper Union at nineteen. Assigned to be a porter, he worked with other men who had been stevedores, who “had the rhythm,” he said. He was so bad a porter his fellow GIs would encourage him to step aside and draw. He’d pull his book and pencil out of his gas mask and draw, as he had done all his life.

When he returned to New York he had an exhibit of those pictures. He said other veterans at Cooper Union asked “When did you have time? and I said, did you expect me not to grow as an artist?”

What he saw during the war in Europe shook him. He enrolled in Columbia University to study philosophy. He wanted to understand why men choose war.

It is clear that he chose peace. He radiates warmth and kindness, quick to give an embrace, careful not to exclude anyone. He always begins a speech by reciting “My People,” by Langston Hughes. Once, seeing white people in the audience, he smilingly said that “my people” are all people.

Though he was talented and passionately committed to becoming an illustrator, he was not published until he was in his forties. He was the first African American children’s book author and illustrator to be published, in 1962. The roadblocks and cruelties he met could have embittered him. He kept creating.

“I never gave up. Many were more gifted than I but they gave up. They dropped out. What they faced out there in the world--they gave up.”

Now in his nineties, he just won a Laura Ingalls Wilder Lifetime Achievement Award. He has won the Coretta Scott King Award for children’s books three times. He is almost as famous for mentoring others as he is for his own work.

Like a musician who plays many instruments, he is versatile. On an island on Maine, he makes puppets, builds stained glass windows from beach glass and papier mache, paints, draws, writes and makes collages.

He encourages others to develop their creativity. “You’ve got to just stand up for what you love, what you love and go to and immerse your life in and want to offer to others. You are doing the works of peace. You are clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, feeding the hungry. Our desire is for peace.”

Ashley Bryans’ autobiography, “words to my life’s song” was just published by Atheneum. It’s in the form of a picture book for children. It is twice the set length of a picture book. They are almost always 32 pages. This is 64 pages. He said his publisher knew it had to be beautiful, so they kept letting him expand it. The gorgeous pictures of his woodblock prints, his island, the covers of his books all had to be included.

Ashley Bryan drew all the time and studied so well that he finished high school in Harlem at sixteen. College officials told him it would be wasteful to give a scholarship to a colored student. His teachers asked him to apply to Cooper Union—a blind test. “You put your work in a tray, sculpture, drawing, painting, and it was judged. They never saw you. If you met the requirements, tuition was free, and it still is to this day,” said Mr. Bryan.

World War II interrupted his education. He was drafted out of Cooper Union at nineteen. Assigned to be a porter, he worked with other men who had been stevedores, who “had the rhythm,” he said. He was so bad a porter his fellow GIs would encourage him to step aside and draw. He’d pull his book and pencil out of his gas mask and draw, as he had done all his life.

When he returned to New York he had an exhibit of those pictures. He said other veterans at Cooper Union asked “When did you have time? and I said, did you expect me not to grow as an artist?”

What he saw during the war in Europe shook him. He enrolled in Columbia University to study philosophy. He wanted to understand why men choose war.

It is clear that he chose peace. He radiates warmth and kindness, quick to give an embrace, careful not to exclude anyone. He always begins a speech by reciting “My People,” by Langston Hughes. Once, seeing white people in the audience, he smilingly said that “my people” are all people.

Though he was talented and passionately committed to becoming an illustrator, he was not published until he was in his forties. He was the first African American children’s book author and illustrator to be published, in 1962. The roadblocks and cruelties he met could have embittered him. He kept creating.

“I never gave up. Many were more gifted than I but they gave up. They dropped out. What they faced out there in the world--they gave up.”

Now in his nineties, he just won a Laura Ingalls Wilder Lifetime Achievement Award. He has won the Coretta Scott King Award for children’s books three times. He is almost as famous for mentoring others as he is for his own work.

Like a musician who plays many instruments, he is versatile. On an island on Maine, he makes puppets, builds stained glass windows from beach glass and papier mache, paints, draws, writes and makes collages.

He encourages others to develop their creativity. “You’ve got to just stand up for what you love, what you love and go to and immerse your life in and want to offer to others. You are doing the works of peace. You are clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, feeding the hungry. Our desire is for peace.”

Ashley Bryans’ autobiography, “words to my life’s song” was just published by Atheneum. It’s in the form of a picture book for children. It is twice the set length of a picture book. They are almost always 32 pages. This is 64 pages. He said his publisher knew it had to be beautiful, so they kept letting him expand it. The gorgeous pictures of his woodblock prints, his island, the covers of his books all had to be included.