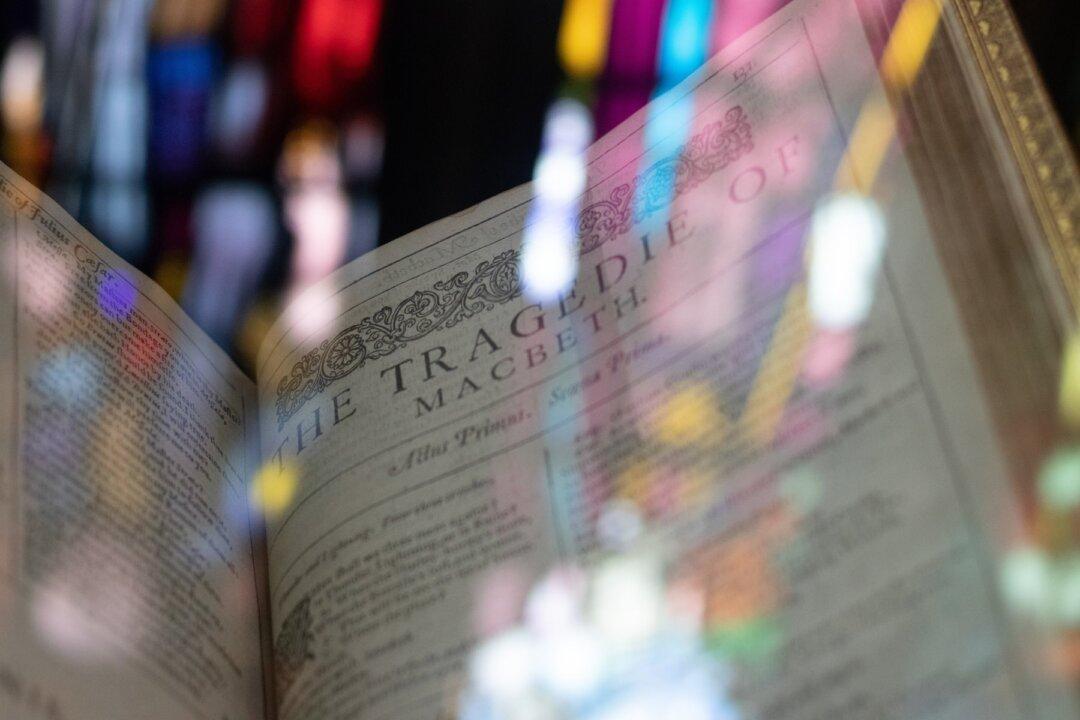

If the very thought of seeing a Shakespeare play, reading one, or—dear, oh dear—memorizing a few of his lines makes you feel light-headed and in need of blotting your forehead, you might be surprised to learn that if you were raised with English as your first language, you’re likely quoting him all the time.

Shakespeare’s legacy goes deeper than one might imagine, to the very marrow of the English language. Expressions that the poet and playwright devised remain in common usage even after the 400 years of his penning them. Consider “It’s Greek to me,” meaning that whatever is being expressed is incomprehensible, whether because it is foreign, complex, imprecise, or belongs to a specialized field outside of one’s domain.