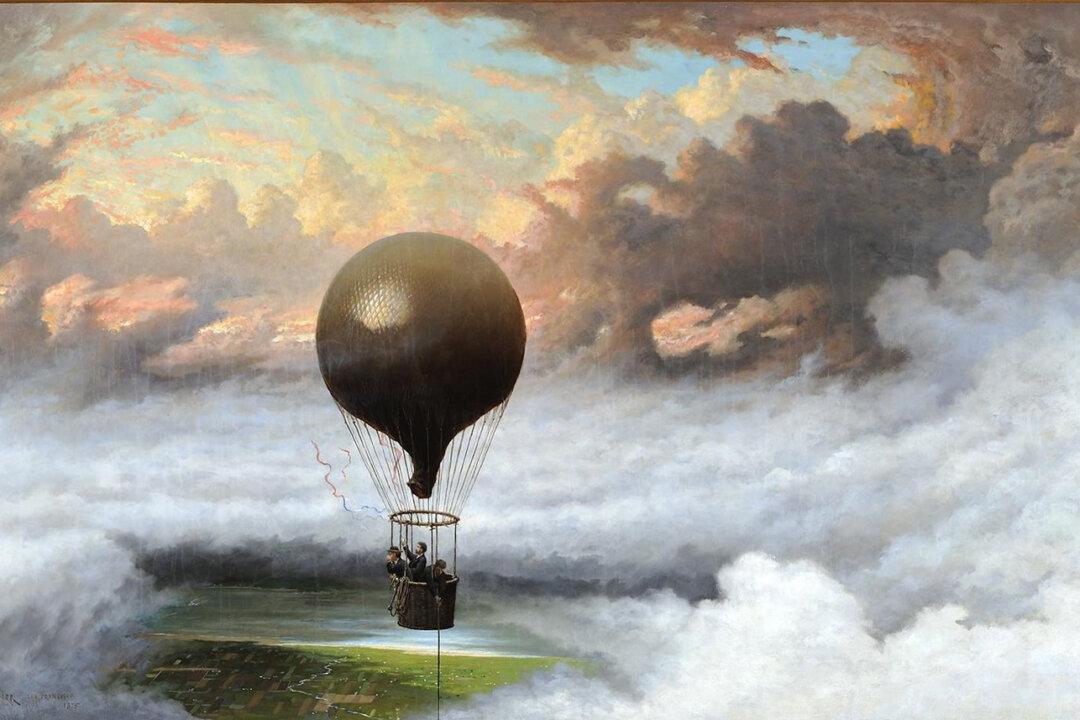

As their helium-filled balloon, Double Eagle, descended rapidly toward the frigid waters off the coast of Iceland, Ben Abruzzo and Maxie Anderson appeared doomed to meet the same tragic end as the five balloonists before them. It was September 1977. The pair had been in the air for 66 hours and had covered nearly 3,000 miles. Since 1783, there had been 13 attempts that failed to make the transatlantic crossing via balloon. Abruzzo and Anderson’s latest attempt found them bobbing up and down on the surface of the Atlantic, working to keep their canopy afloat and trying unsuccessfully to stave off frostbite.

Unlike some of those previous attempts, Abruzzo and Anderson had the capability to radio for help. Soon a rescue helicopter could be heard in the distance. The two returned to the United States to recover, and then began making plans for a 15th attempt.