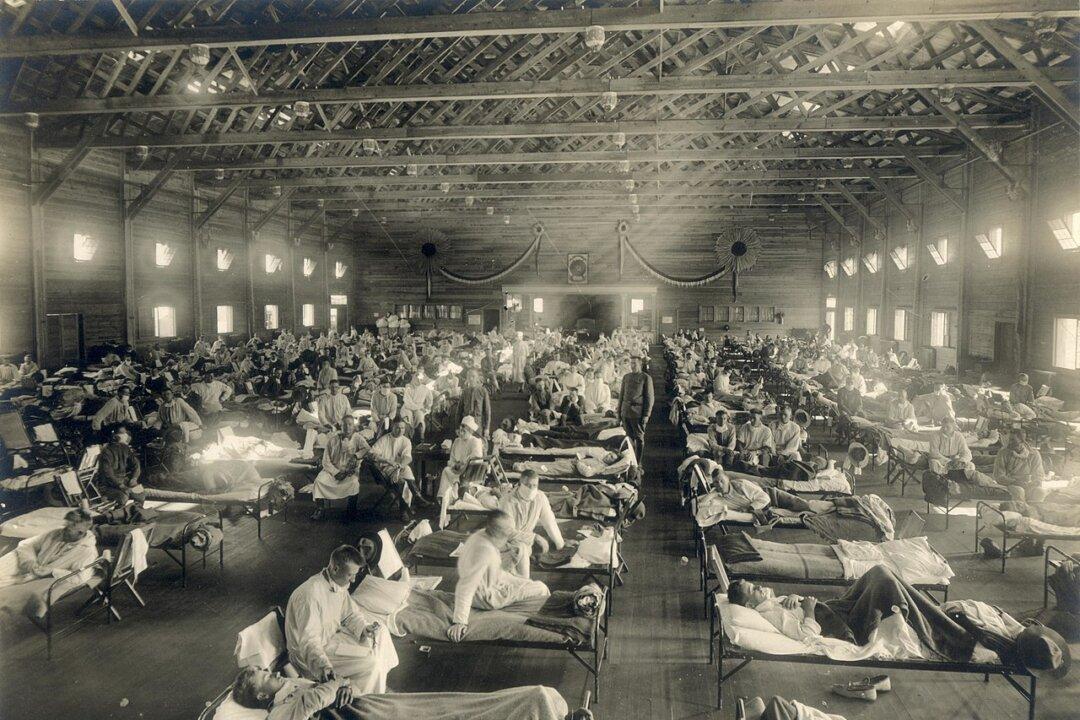

World War I wasn’t the deadliest event of the 1910s.

That designation belongs to what some have called “the forgotten pandemic,” a global outbreak of influenza in 1918 that not only outstripped World War I’s mortality rate, but might even be the single deadliest event in recent human history.