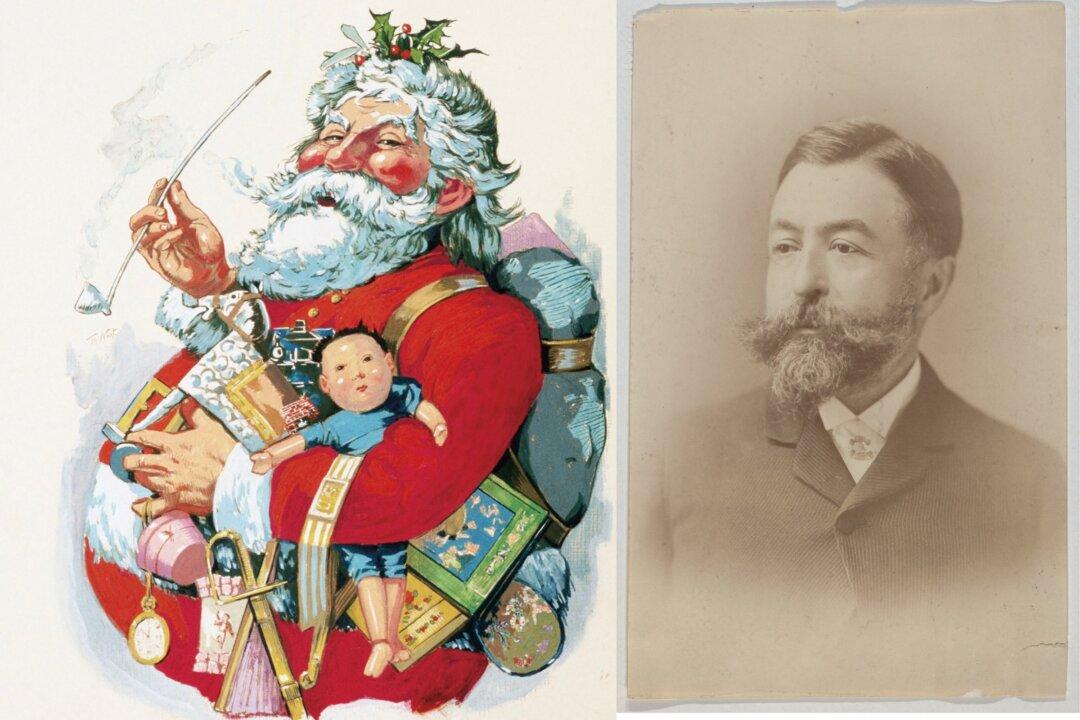

The legend of Santa Claus is centuries old, but the jolly guy’s use of the North Pole as home base for making toys, checking his list of good girls and boys, and prepping for his Christmas Eve rounds has only been common knowledge for just over 150 years.

The North Pole was first identified as Santa’s home by Thomas Nast. Nast was a 19th-century German-born caricaturist who did editorial cartoons depicting the contemporary politics of his time. Commonly referred to as the Father of the American Cartoon, his background seems antithetical to someone doing detailed illustrations of Santa Claus, elves, and reindeer. Yet how we see Santa Claus and the North Pole today is a direct influence of Thomas Nast’s Christmas illustrations.