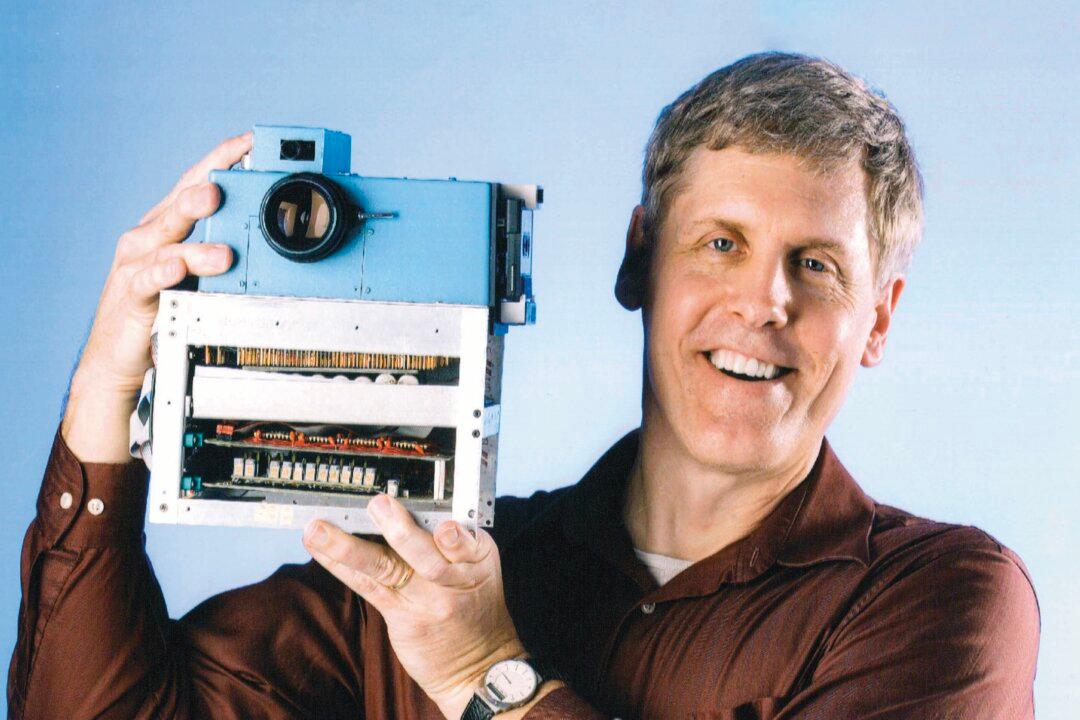

Digital cameras are everywhere today, and they all trace their lineage to a device about the size of a toaster that was invented in 1975 by Steve Sasson. At the time, he was a young engineer at Kodak.

Born in 1950 in Brooklyn, New York, Mr. Sasson developed an early interest in chemistry and electronics. He taught himself how to operate a ham radio at 13. “I was interested in electronics and doing chemistry experiments, but those tended to get me in trouble because they created a lot of smoke,” he laughed. He stuck with electronics. After graduating from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute with an electrical engineering degree, Mr. Sasson was hired by Kodak in 1973. Though the company was firmly entrenched in film-based technology, they were also interested in new research and development. “Kodak was becoming involved with electrical electronic components, like exposure controls, flashes, and film advance, so they started looking for electrical engineers.” Mr. Sasson’s first job in Kodak’s research lab was to build a control system for a machine that would clean movie camera lenses. After completing the assignment, he was offered the chance to experiment with a new type of imaging device, which would become the basis for digitizing images. “You would expose a pattern of light on the surface of this device about the size of a thumbnail. It would then generate a corresponding charge pattern. Where there was a lot of light, you have a lot of electrons separated into packets—we call them pixels now.” He used numbers to represent the light pattern. “So I have a digitized version of the image on the device. If I could store that permanently, I would be duplicating what a camera does. That was the idea of the digital camera.”

He was inspired by the futuristic possibilities that were shown on the hit TV show “Star Trek.” “There was no paper or film on the bridge of the Enterprise, there was just electronic communication. That represented the vision of the future and inspired my goal to develop a filmless camera that would take and display an image.”