It wasn’t anticipated that James K. Polk would become the next president. The favorite among the Democratic candidates was the former president Martin Van Buren; but he wasn’t favored to win the election of 1844. He had already been defeated in 1840 by the now deceased Whig, William Henry Harrison, who had lasted only 30 days, 12 hours and 30 minutes in office. Vice President John Tyler had become president, and, by 1844, was rather unpopular with both Whigs and Democrats. The Democrats didn’t want Van Buren. The Whigs didn’t want Tyler. Therefore, Tyler, the sitting president, threw his support behind America’s first “dark horse” candidate: James K. Polk.

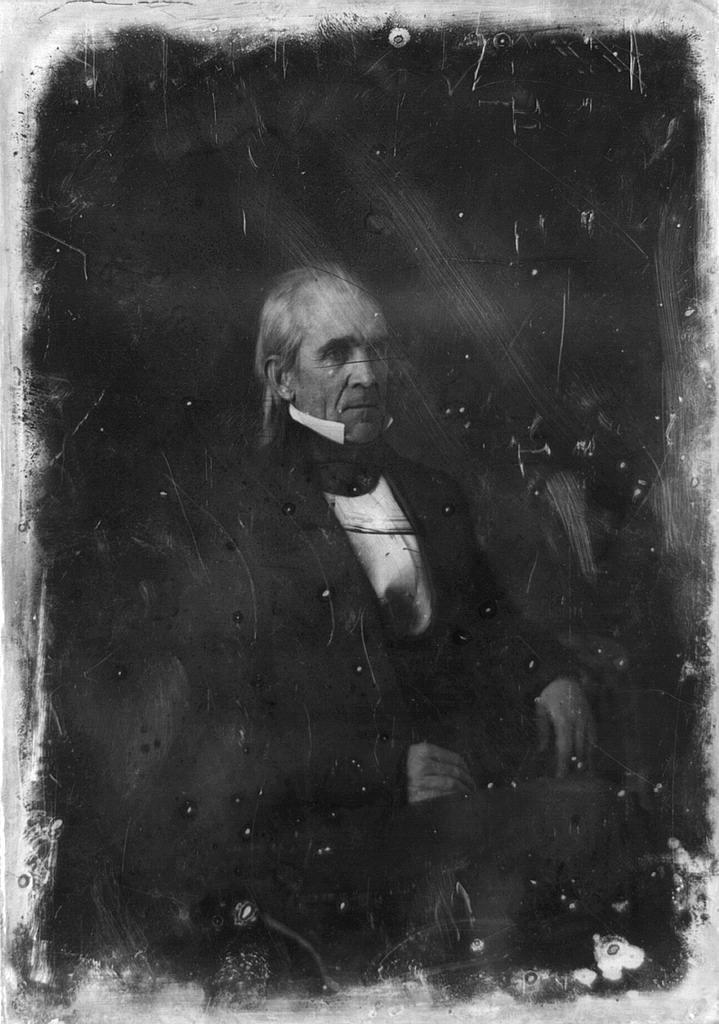

The first president to be photographed while in office: James K. Polk, in 1849. Library of Congress. Public Domain