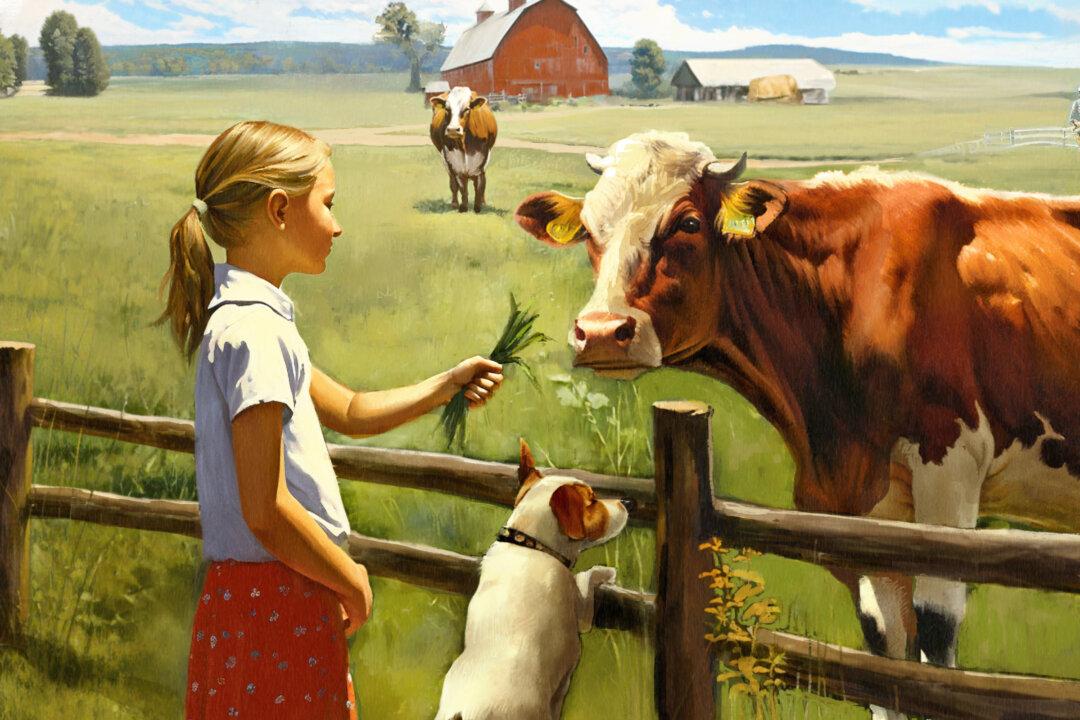

My daughter used to cry when the cows approached to eat some apples over the fence from my wife’s hand. But now she just watches them, their slow, powerful movements, as they lumber down the hillside for some tasty scraps.

My daughter isn’t quite a year old. But I hope that, as she grows older, the cows will become a fascinating fixture in her life—other living beings that aren’t like her or her mom and dad; creatures that somehow transform the grass outside into warm, creamy milk to accompany her breakfasts; creatures that meander along the slope that leads up to a tree line of pines that creak and sigh in the wind; a backdrop of stable and peaceful life encircling her own.