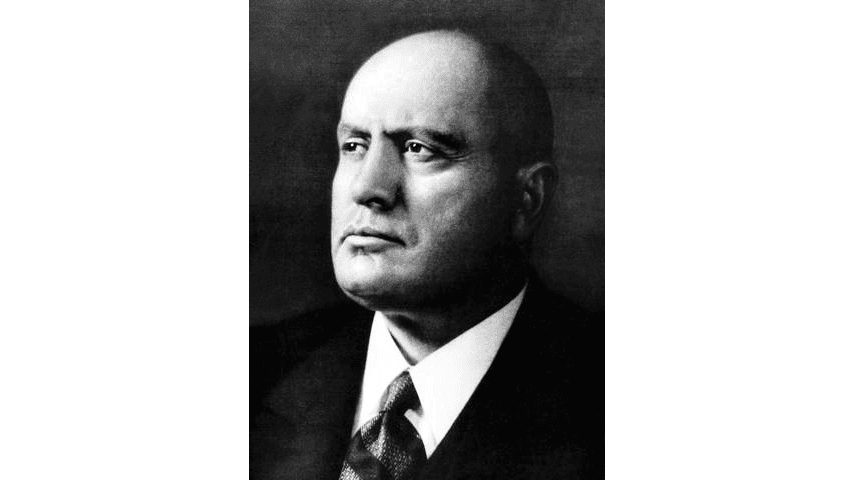

In 1919, Benito Mussolini looked like just another failed politician.

His defeat seemed so complete after he lost his seat in the Italian Chamber of Deputies that his socialist opponents carted around a coffin symbolizing, they said, the death and burial of Mussolini’s career.