In 1969, the world watched the Apollo 11 mission with bated breath. For Margaret Hamilton and her team, the view was a little different; they watched the landing from the monitoring room at MIT. Moments before the module was supposed to land on the moon, the computer started flashing warning messages. Everyone’s heart stopped as the emergency registered. In an instant, however, it became clear that the problem was fixing itself and that Hamilton’s work had saved the mission. The software she wrote with her team was not only informing everyone about the problem, but actively compensating for it by restarting the program and focusing on the only thing that mattered: landing the module safely. Minutes later, Neil Armstrong reported that “The Eagle has landed.”

A New Field

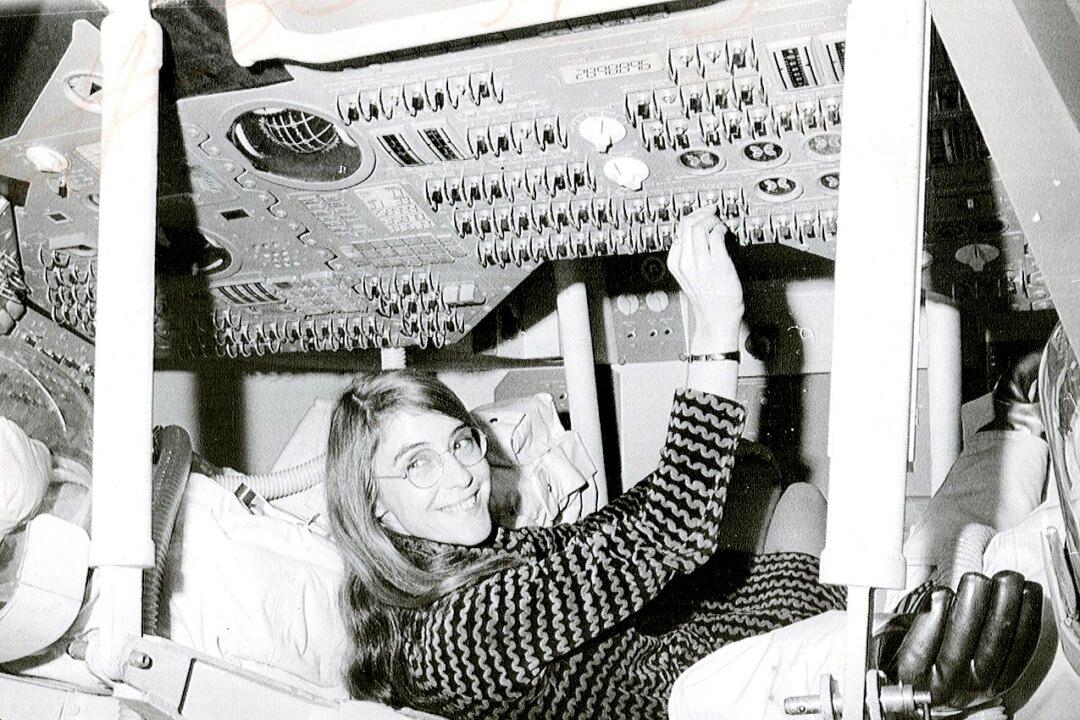

Born in 1936 in Paoli, Indiana, Margaret Hamilton never imagined that she would become a computer scientist, much less one who would be remembered in American history. The modern computer wasn’t even built until seven years after her birth. Hamilton studied mathematics and philosophy at Earlham College in the 1950s, where she met her husband. Hamilton initially intended to teach high school mathematics, but her plans changed when she moved with her husband to Boston so that he could study law at Harvard. In order to support the family, Hamilton took a job for a project at MIT while her husband worked on his degree. The project, run by professor Edward Lorenz, involved creating a system to predict the weather. Lorenz had advertised specifically for math majors, and Hamilton fit the bill. Under his guidance, she learned what a computer was and took on the challenge of writing software. She learned on the job, and she was inspired by Lorenz to continue experimenting with software.Fascinated by software programming and eager to experiment in such a new field, Hamilton went on to work for MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory in the early 1960s. Here, she continued to learn about and practice programming while working on the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) project, a system used to identify enemy aircraft. Hamilton’s experience with software programming made her a perfect candidate for the job on the Apollo 11 mission, and she was the first to apply after seeing it advertised in the newspaper.