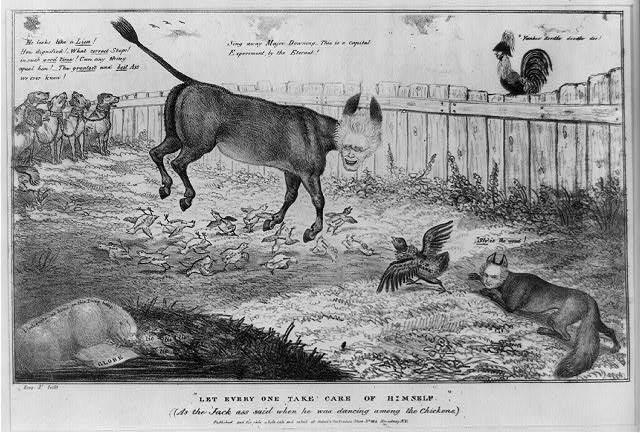

The opponents of Andrew Jackson had a nickname for him: “Jack-ass.” Perhaps it was a play on words from his last name or maybe it was simply as crude as one could get without being obscene. Either way, the name stuck throughout his presidency from 1829 to 1837.

"Let Every One Take Care of Himself" is a political satire of Andrew Jackson, whose face is shown on the jackass's head. Library of Congress. Public Domain