Before, during, and after World War I, President Woodrow Wilson believed it was his and America’s destiny to lead Europe to lasting peace. When he stood before Congress on Jan. 8, 1918, he presented his now famous “Fourteen Points.” Among those points, he called for the self-determination of individual nations and the “general association of nations.” It was this latter proposition—his 14th point—that proved to be the demise of Wilson’s vision.

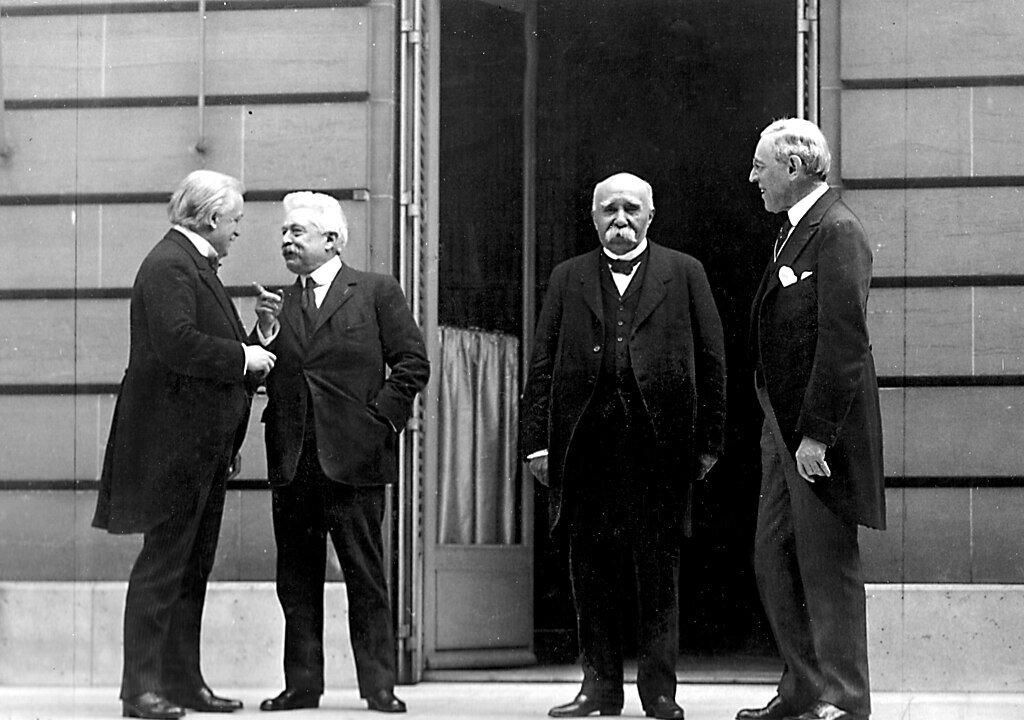

A month after the armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, which ended hostilities, Wilson arrived in France. He had committed himself to the unprecedented act of spending more than six months abroad. He, along with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Prime Minister George Clémenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (who would resign during the peace process), would lead the Paris Peace Conference that ultimately culminated in the Treaty of Versailles.