Chinese artisans had already been making porcelain for thousands of years when Venetian merchant Marco Polo first brought porcelain from China to Europe in the 14th century. Polo’s discovery started Europe’s enduring love of porcelain.

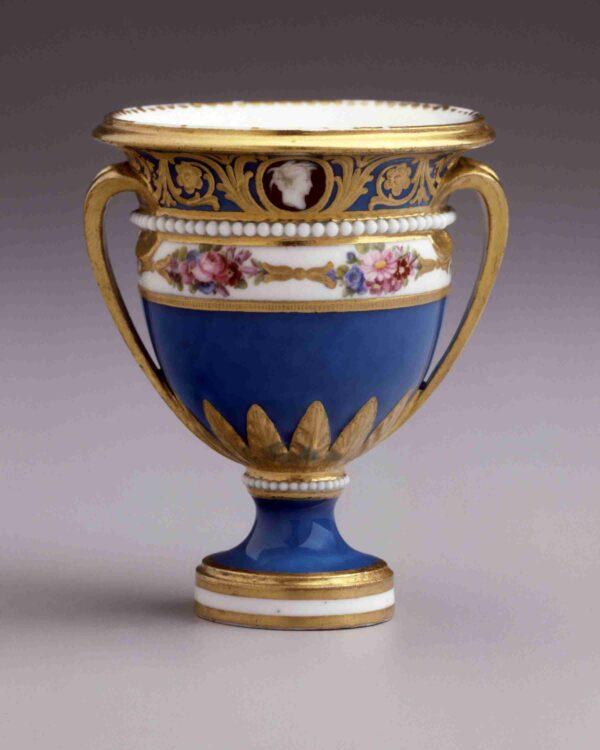

Ice cup from the Cameo Service, circa 1779, by Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, Sèvres, France. Soft-paste porcelain; 3 1/2 inches tall. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens. Edward Owen/Courtesy of Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens