It’s doubtful that the private thoughts and curiosities of Leonardo da Vinci would have survived without the diligent preservation efforts of his favorite pupil, Francesco Melzi. When da Vinci died in 1519, all of his manuscripts―or as da Vinci called them, “a collection without order”―were left to Melzi.

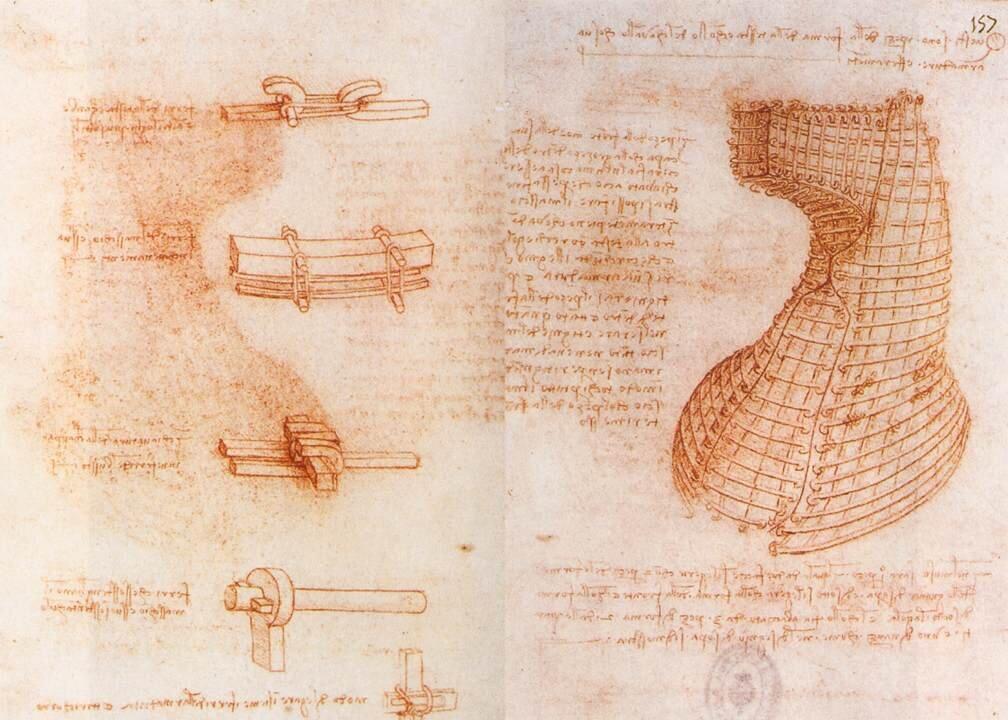

Francesco Melzi, disciple of Leonardo da Vinci, 1510-1511, by Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. Public Domain