A month before Abraham Lincoln took office as the country’s 16th president, seven states had already seceded from the Union. Thirty-nine days later at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861, Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, where Union troops had been stationed. The Civil War had begun.

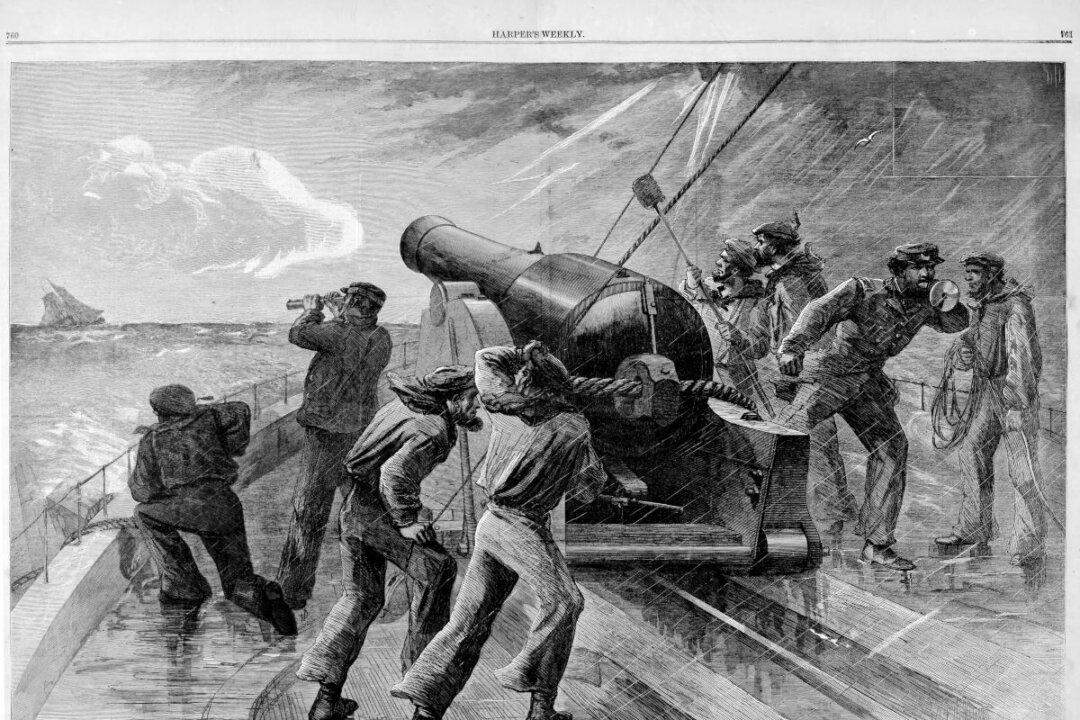

A week later, on April 19, Lincoln proclaimed a “blockade of the ports” of those states along the southern Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico seaboard: South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.