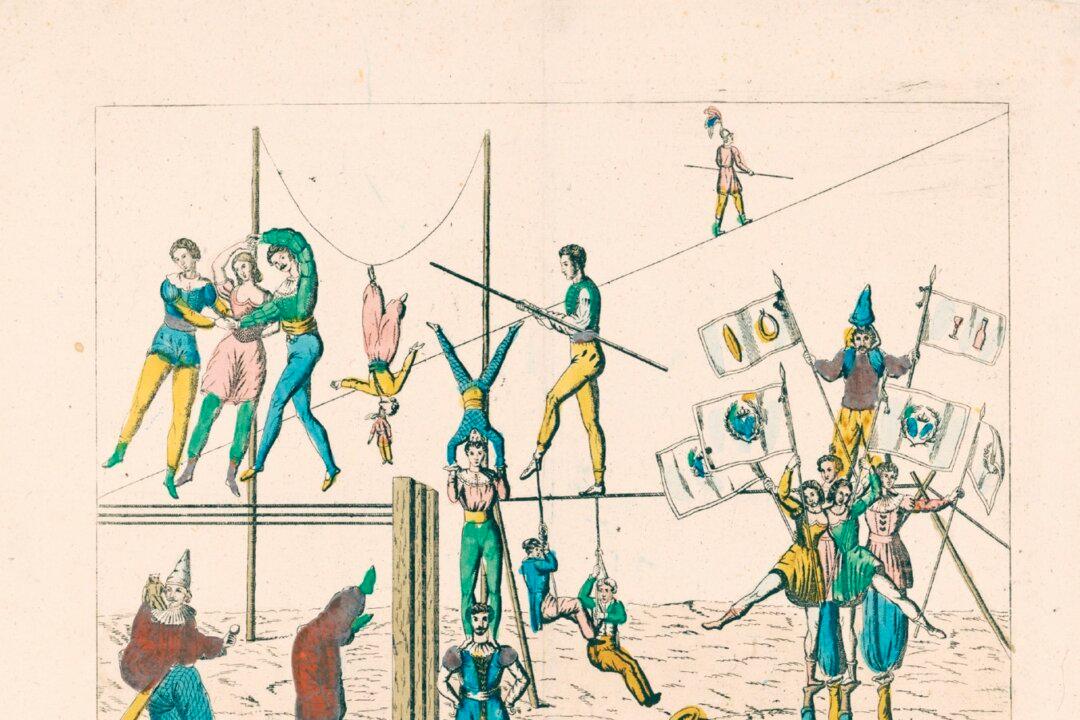

It is recorded that in 1793, George Washington went to the circus in Philadelphia, perhaps one of the first circuses in America. It was, by all accounts, mainly an equestrian show. It did have jugglers, clowns, and even a rope walker. Around 1825, American circuses began to use tents. As they added animals and equipment, they traveled by horse-drawn wagons. On April 10, 1871, Phineas T. Barnum opened his circus under 3 acres of canvas in Brooklyn, New York. In the decades to follow, circuses would travel by special trains, which were needed to carry the vast troupe of human and animal performers.

The same Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 that brought the great White City’s classical architecture to the main streets of so many American towns also brought them the “midway,” a term borrowed from the Chicago fair’s entertainment district—the Midway Plaisance. The Midway’s fair showcased the exotic and the unusual. The great Ferris Wheel was not in the White City, but rather on the Midway Plaisance. The years following the great fair saw a proliferation of traveling shows that brought “the world” to small-town America. They ranged in size from the great tent circuses to the smaller carnival companies that would do the circuit of state and county fairs—occupying the midway.