When the 1893 Columbian Exposition opened on the shores of Lake Michigan, visitors to the fair were treated to a glimpse of the future. Chicago, the great classical “White City” by day, at night became a magically illuminated world of colored lights.

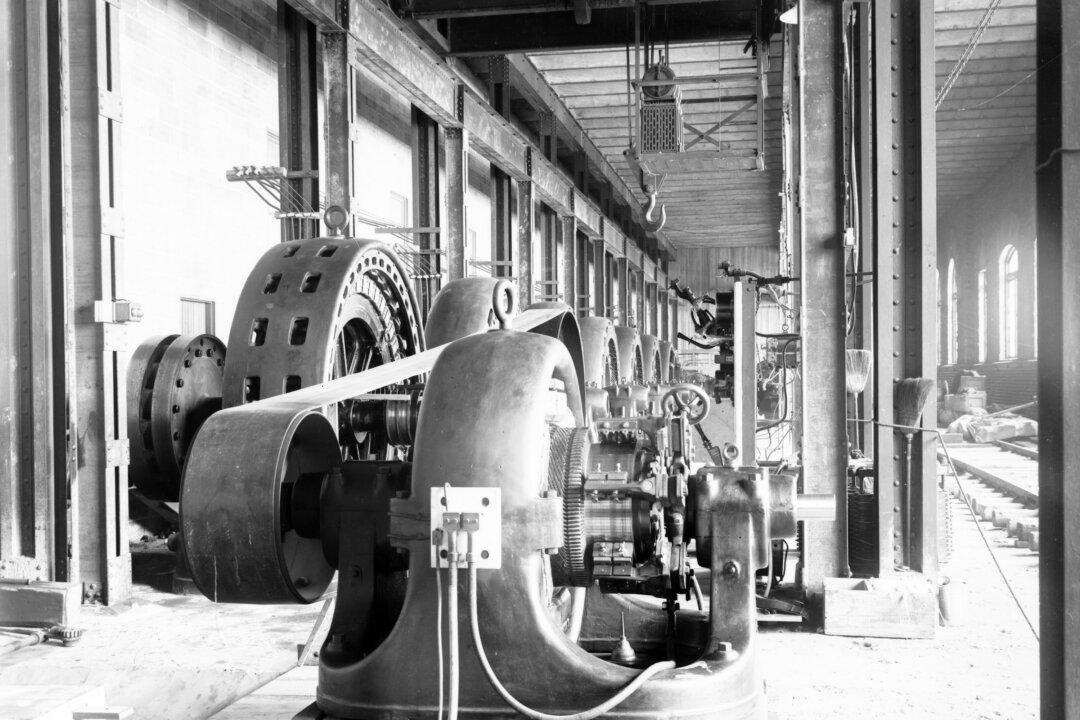

President Grover Cleveland opened the exhibition by pushing a button that set the great dynamo engine in motion with its alternating-current generator providing power to thousands of incandescent bulbs. At that moment, America first saw the promise of electricity on full display.