To placate his agitation during World War II, Winston Churchill frequently recited one of his favorite poems. Written by Thomas Babington Macaulay in 1842, “Horatius” earned young Churchill first prize in a competition of recitation by memory at Harrow School. The 70 stanzas that impressed the competition’s judges would stay with the British prime minister for the rest of his life, inspiring him to find courage in dire straits and lead with hope and resilience. Horatius’s story reveals why the poem was a fount of strength for Churchill, and why it can be one for us today.

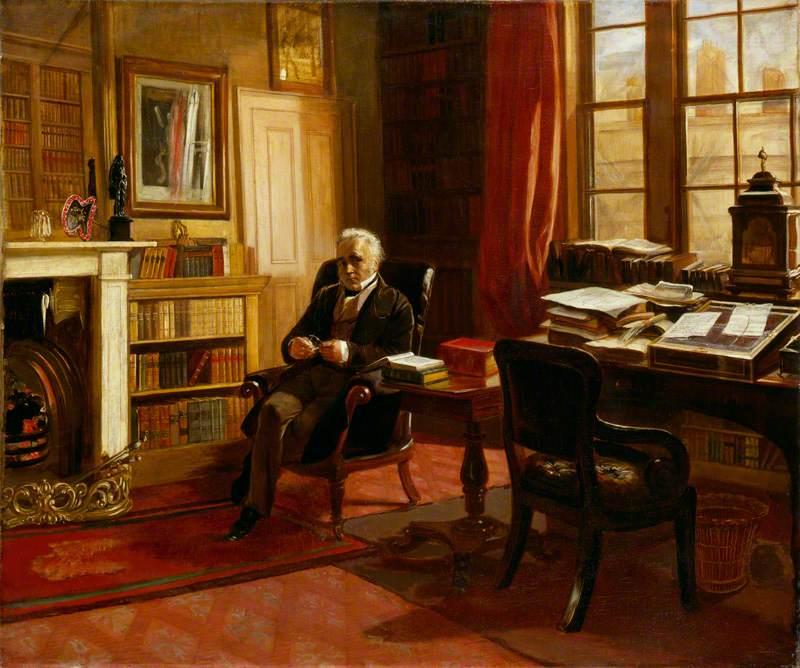

"Thomas Babington Macaulay," 1853, by Edward Matthew Ward. Oil on canvas; 25 inches by 30 inches. National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain