For millennia, the ancient Greek epic poems the “Iliad” and the ”Odyssey” have profoundly influenced readers, scholars, authors, and artists, and they are universally regarded as two of Western civilization’s foundational literary texts. The basis of both stories is the Trojan War, which was precipitated by Helen, queen of the Greek city-state of Sparta, leaving her husband and taking refuge in Troy with Paris, a prince of that city.

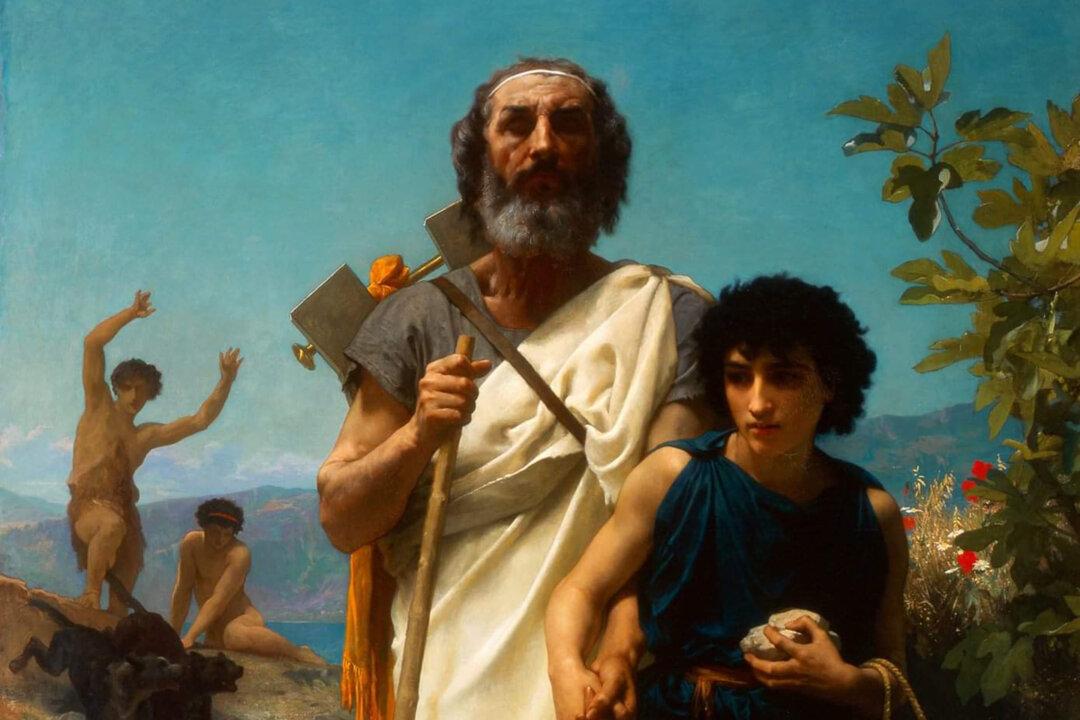

The “Iliad” is set in the 10th year of the resultant war between Troy and the Greek city-states. The war ends with the siege of Troy by the Greeks. The ”Odyssey” follows the turbulent journey of one of the war’s Greek heroes, Odysseus, King of Ithaca, on his voyage home. It takes Odysseus another 10 years to return to Ithaca as he craftily contends with various impediments. In the meantime, his queen, Penelope, uses her own guile to avoid remarriage, hopeful that her husband will one day return. In both of these poems, characters, relationships, and scenes of honor, danger, and temptation are masterfully brought to life by their poet, the legendary Homer.