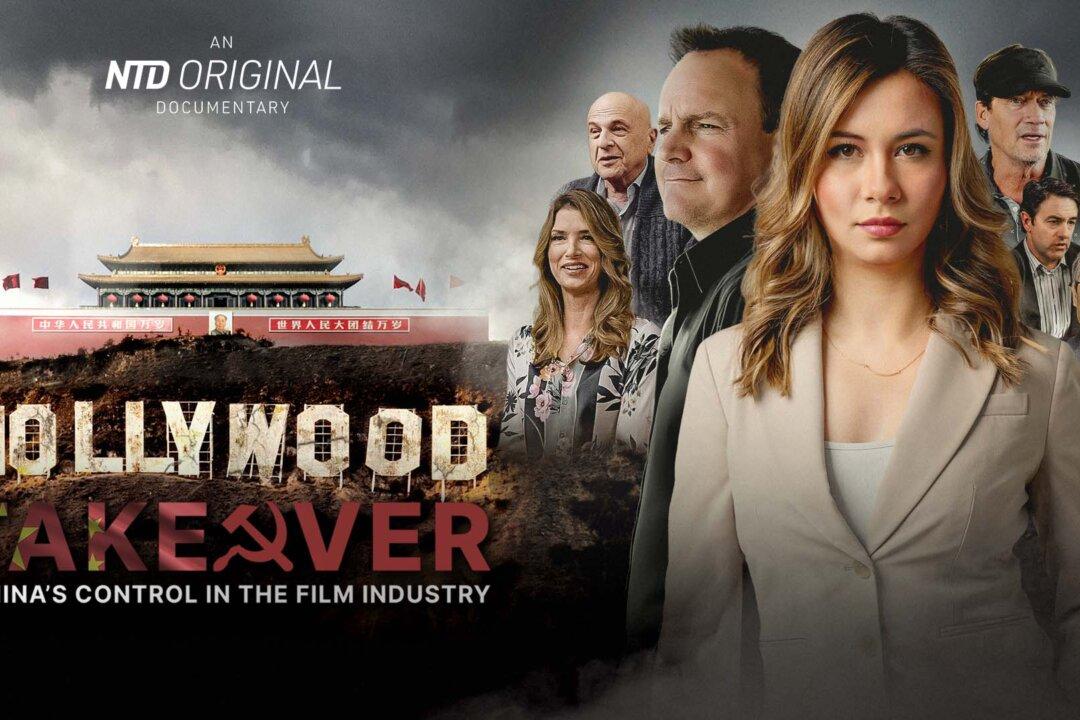

NR | 1h 4m | Documentary, Film, Politics | March 8, 2024 (USA)

During the opening title sequence of “Hollywood Takeover: China’s Control in the Film Industry” (“Takeover”), a title card includes a quote from Mao Zedong, the sixth through 10th chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It reads “There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake,” an obvious slam against the text “ars gratia artis” (Latin for “art for art’s sake”) surrounding the “Leo the Lion” logo at the start of all MGM studio productions.