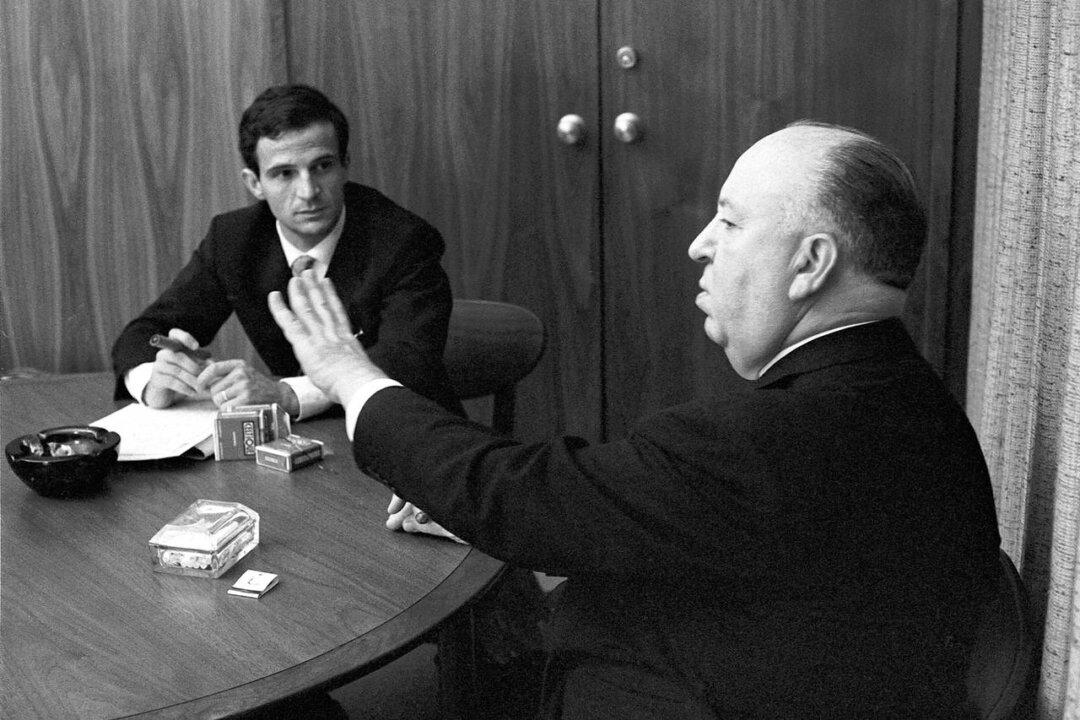

PG-13 | 1h 20m | Documentary, Biography, Film History | 2015

In 1962, Alfred Hitchcock received a handwritten letter from François Truffaut that asked him to participate in week-long interviews for a book Truffaut was writing about Hitchcock. It wasn’t going to be a biography, but an in-depth analysis of Hitchcock’s entire filmography up to that point.