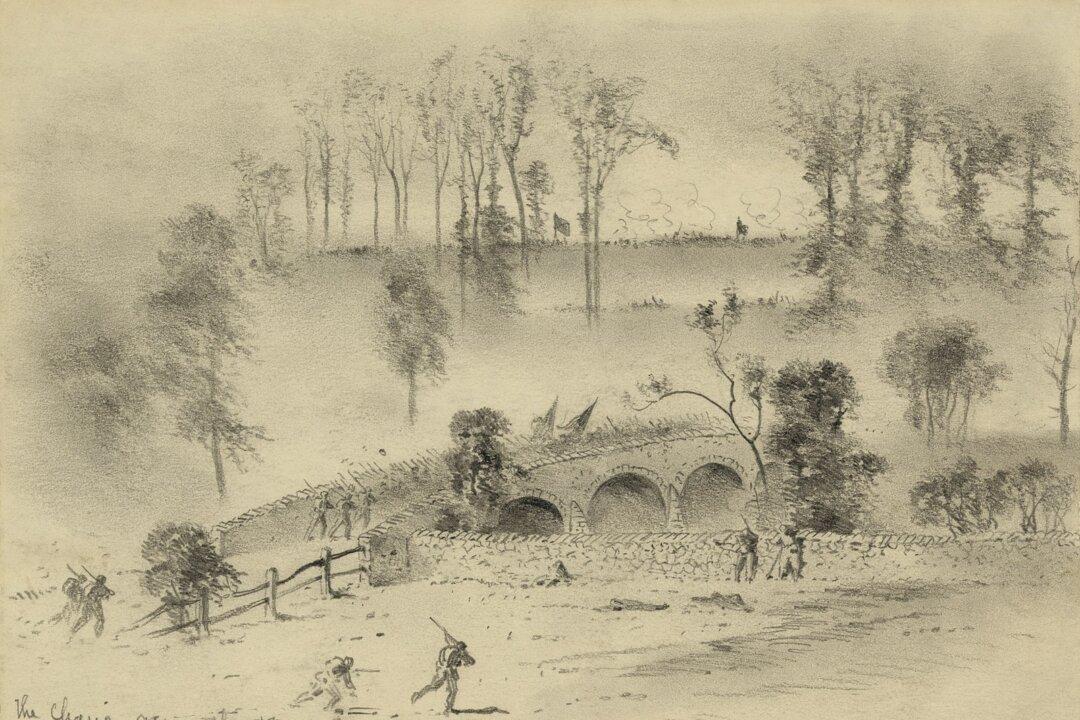

Washington County, Maryland, was established in 1776. It was named for the Revolutionary War general who became the first U.S. president. For many years, a bridge over a small creek in that county served people between the farming communities of Sharpsburg and Rohrersville. But when Confederate and Union soldiers met there Sept. 17, 1862, there were major historical implications. The name of what was called Rohrbach (or Lower) Bridge crossing Antietam Creek changed forever.

Finding this tucked-away locale isn’t easy; it’s not often on travelers’ radars. Burnside Bridge now sits on property owned and managed by the National Park Service, thanks to the formation of Antietam National Battlefield in 1890. It’s situated away from the cemetery, Sunken Road, cornfield, and woods where the bloodiest single day of fighting of the entire Civil War occurred.