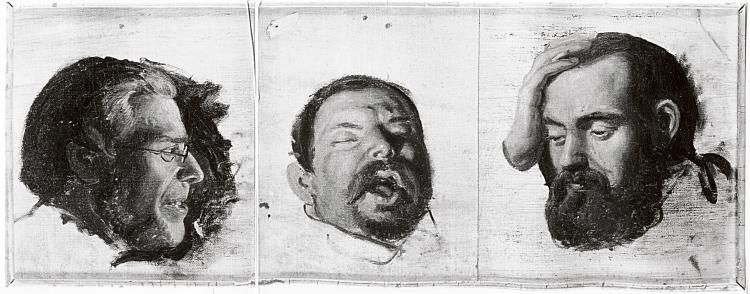

Three faces on a piece of canvas: A shocked elderly man at the left, staring at a dead man in the middle from whose mouth fresh blood is running. On the other side a desperate bearded man with a tear running down his cheek.

Is this an authentic picture? The owner asked Professor Siegfried Wichmann on a November day in the year 1967. It’s a routine question for the chief curator of Munich’s Bavarian State Painting Collection.

It was no doubt for Wichmann, the 19th century expert, that this was truly a Hermann Kaulbach sketch. The dynamically rounded stroke renders the faces with ease and accuracy.

The canvas showed traces of raindrops, as if the painter had worked in the rain. On the backside he found three names: “S. von Löwenfeld”, “Ludwig II” and “Hornig.”

The broad, soft face with the characteristic beard left no doubt for Wichmann, that this was a life portrait of the dead King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

A Painful Memory

“He was shot!” it flashed through his mind. Wichmann, who had suffered severe lung damage in World War II, was alarmed by the blood coming out of the King’s mouth. The picture painfully reminded of his own near-death experience.

Following his usual routine, he took a photo of the sketch, filed it for the archive and gave the painting back. The fact that he had seen the evidence picture for the King’s murder struck him. He tried to contact the man with the picture a few days later—but painting and owner were not to be found.

Meanwhile, the official explanation for the king’s death was as follows:

Ludwig II had fallen into incurable mental illness, was divested from his office, arrested and committed suicide in the waters of the Starnberg lake after killing his “psychiatric doctor” Bernhard von Gudden, who had been walking with him on the lakeside on the evening of June 13th, 1886.

This story was woven into the textbooks in such a convincing way, that it’s hard to believe that it was actually a group of corrupt ministers and military staff that had planned and successfully conducted the fall of the completely healthy and highly popular monarch.

Years later, in 1982, Wichmann found out that the inheritance of Schleiss von Löwenfeld, the old man from the picture, was auctioned.

An Incredible Chance

Maximilian Schleiss von Löwenfeld was the king’s personal physician and was fired from his position after the circle of conspirators had elected the psychiatrist Gudden for that position.

The old man had been loyal to his king even after his death. He made his point public in the newspaper: “Of the existence of a severe illness, that would have permanently hindered His Majesty from fulfilling the governmental duties, M. Schleiss von Löwenfeld is definitely not convinced.”

As his autobiographic notes tell, soon he had to publicly revoke his statement, as the conspirators had forced him with death threats.

Wichmann joined the thrilling auction on the phone. He had 36 people, included the King’s family—against him. Between them was a bunch of old books, letters, and paintings. He instinctively knew that this was the rare chance to get first hand information of a historic source, so he was ready to pay the price of a family home for it.

His intuition was right: Hidden in a book cover, he found Löwenfeld’s recordings of what he saw on June 13th. The notes were written in an abbreviated old German handwriting style, overlooked as nobody had decrypted it, but Wichmann could read them.

The True Story of June 13th

After being divested from office and arrested three days prior, Ludwig was being kept in a small castle by a lake in the countryside. Having long suspected that danger was upon the King, Löwenfeld, the painter Hermann Kaulbach, and the two Hornig brothers had come to the lakeshore by boat on the evening of June 13. They concluded from the enemies’ activities that something would be happening that evening. They wanted to help the King escape to the other side of the large lake and arrived just a few minutes late: Ludwig had already been shot in the back.

The four caught the psychiatrist Gudden 20 meters from the water changing the King’s clothes and trying to stop the blood flowing out of the wound. According to Löwenfeld, Gudden ran up to them holding a syringe in his hand. After a life and death struggle, Gudden was strangled by the Hornig brothers.

Then, the painter Kaulbach took out his pocket painting case he always had with him and drew the sketch of Ludwig’s face. He kneeled down beside him and put the canvas on his breast. The proximity explains the extreme perspective of the portrait.

When it started to rain, the friends took Ludwig’s body via boat into a nearby fisher’s hut, were Kaulbach finished painting. The hut where they said goodbye to their king was torn down only days later. Kaulbach later added the other two heads of Löwenfeld and Hornig at home.

Because Gudden’s death came unexpectedly, it took the puzzled conspirators some hours to come out with what became the official version of the story.

Gudden was buried without any noise on the graveyard of a small village the next day. To cover up their guilt, the murderers staged a state funeral of enormous expense for the King.

This was the bloody end of the chase against the monarch that had lasted almost two decades.

A Complex Plot

In those days, the only legal way to get rid of a king was to declare him to be mentally ill.

As King Ludwig’s younger brother Otto I had suffered mental illness since his birth, the circle of corrupt ministers, led by Baron von Lutz, had prepared the coup by declaring the King to be a psychopath.

The psychiatric doctor Bernhard von Gudden would become their accessory. Promising to boost the doctor’s career, Lutz got the ambitious Gudden into the game.

The first step was to make up stories about Ludwig. So the conspirators started spying on him day and night, trying to find evidence of illness and unusual behavior. It is true that Ludwig at one point started to sleep during the day and working through the night to avoid contact with the hostile ministers and personnel. He became frustrated and suspicious of the permanent espionage.

A key person in the lie against Ludwig was Duke Holnstein, head of the equerries and a notoriously violent person. He forced his 86 subordinates to make up stories about Ludwig’s supposedly insane behavior. What came out were lies of the most disgusting sort. Fearing Holnstein’s rage and mistreatment, the grooms wrote papers full of slander.

This catalogue of lies was brought before the Bavarian parliamentarians who should decide whether the King was “healthy” or not.

Modern psychologists dealing with the supposed illness of Ludwig II also draw their conclusions from these reports.

Envy Towards the Genius

There was a enormous gap in the realm of thought between the greedy conspirators and the highly educated multilingual Ludwig, who saw his life as king as a mission to establish culture and bestow the nation with things of remaining worth. He was known for his peaceful attitude towards everybody and even tragically promoted his own enemies. He twice refused to get Bavaria involved in war. He was enormously capable as a manager who could run the daily political issues and several castle constructions at the same time. He gathered the most talented artists around him and visited every European World Expo to find out about latest technological inventions.

Following his inner vision of divine right of sovereignty, which was based on his Christian beliefs, he guided the construction of castles such as Neuschwanstein, and shaped Bavaria’s cultural identity like no other ruler has.

Compared to him, his enemies were miserable nobodies: Indignant people that were driven by self-interest, greed, and envy.

Taking the splendid peacock porcelain sculptures that Ludwig had commissioned for the castle Linderhof for example, Wichmann mentioned:

“These people were all so ignorant and narrow minded! Imagine, if they heard him speaking about the peacock as a symbol of immortality in oriental culture—they must have considered him to be crazy...”

Eighty-eight-year-old art historian Prof. Siegfried Wichman is a world-renowned expert on 19th century painting. He has been the longtime chairman of the Bavarian State Museum, and has been researching the life and death of Ludwig II for over 29 years. He held lectures on the Ludwig murder at the Bavarian Police Academy, at their invitation.