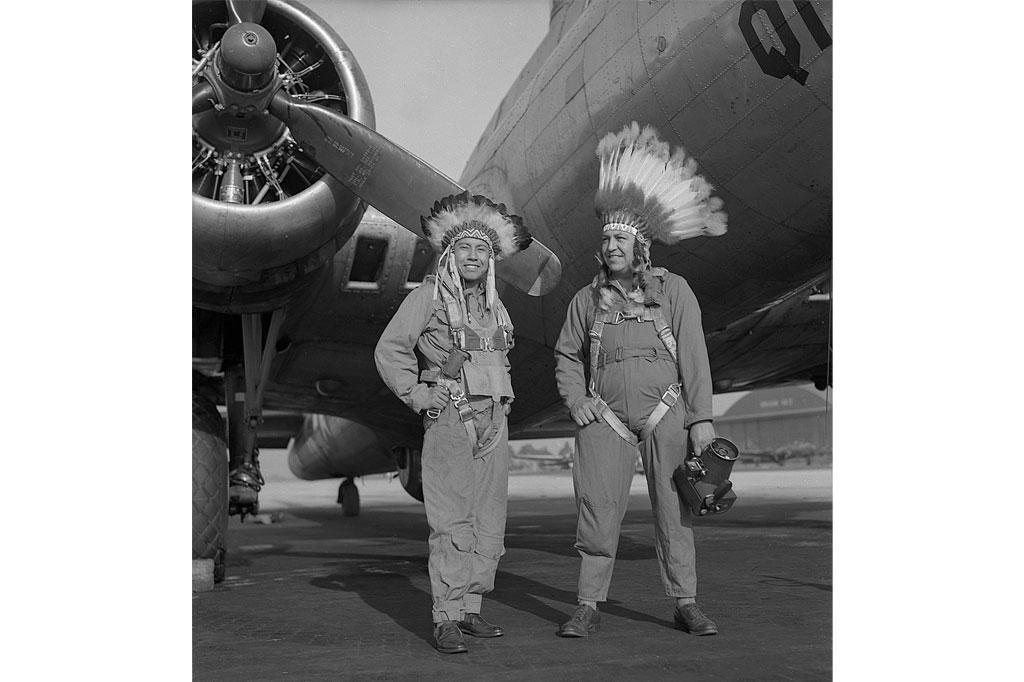

NEW YORK—One became the Van Cleef & Arpels of Navajo jewelry making, and the other lived the Native American experience in epic proportions. The achievements of two extraordinary families, the Yazzies (Navajo) and the Poolaws (Kiowa), are the focus of two recently opened exhibits at The National Museum of the American Indian in New York.

While the museum’s permanent exhibit, An Infinity of Nations, feels thoroughly Smithsonian with its showcase of tribal artifacts from throughout North and Meso-America, the new exhibits zero in on, make personal, and bring up to date modern and contemporary Native American life.

Raymond, Mary Marie, and Lee Yazzie in front of their grandparents' Hogan, a traditional Navajo home, near Gallup, N.M., in 2008. Their mother, Elsie Yazzie, taught jewelry making to her children, nine of whom are jewelers today. Kiyoshi Togashi