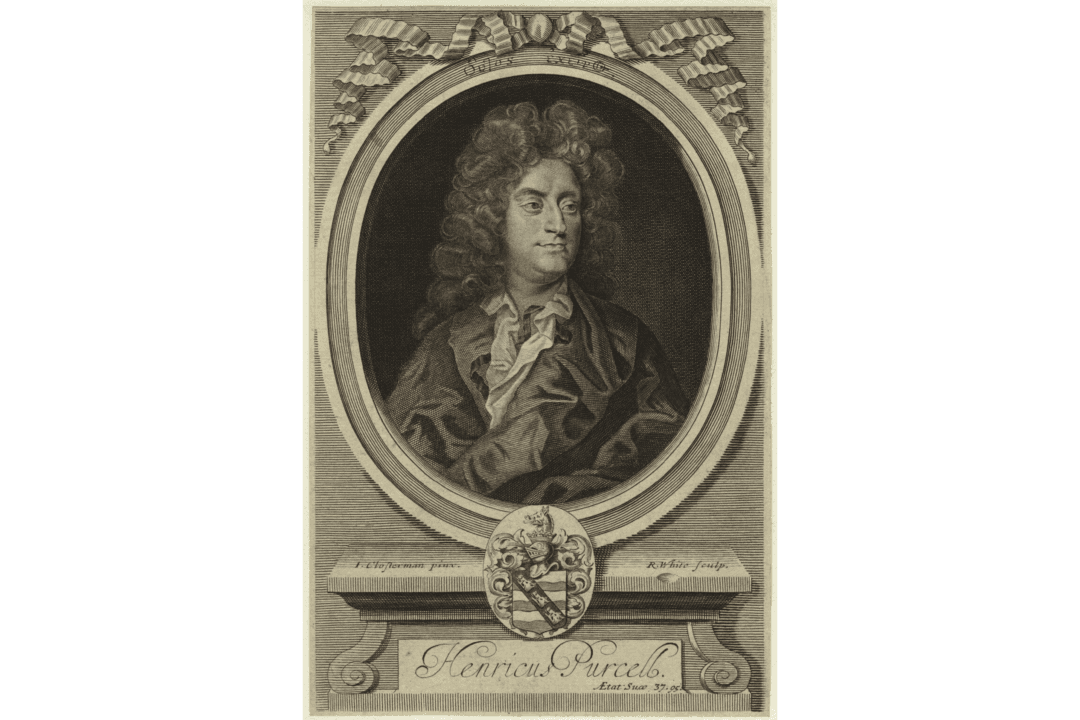

Henry Purcell is widely considered to be the greatest composer England ever produced. Though he died young, he was extraordinarily prolific, writing more than 600 works in his brief life. From operas to songs to chamber music and incidental music for plays, his legacy looms large. Among the very best of these pieces is the music he wrote upon the death of his beloved patron and queen, Mary II.

A Composer Through Three Reigns

Purcell lived through hectic times. He was born in 1659, the year Oliver Cromwell’s son, Richard, abdicated and England’s government became unstable. The nation’s musical life had suffered during republican rule. Puritans restricted public secular music and forbade instrumental music in church. Choirs were disbanded and congregations only sang Psalms and biblical cantatas.With the return of Charles II in 1660, the son of the monarch whom Oliver Cromwell had beheaded, these bans were lifted. Purcell’s talent was discovered early when he was chosen to be in the Chapel Royal choir at the age of 8. After his voice changed, he continued at Westminster Abbey as an organist in a music career that spanned three reigns. After Charles II died, he served James II. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688, James’s fortunes fell when he was deposed. Purcell’s star rose higher, however. After William and Mary ascended the throne, he was appointed court composer.