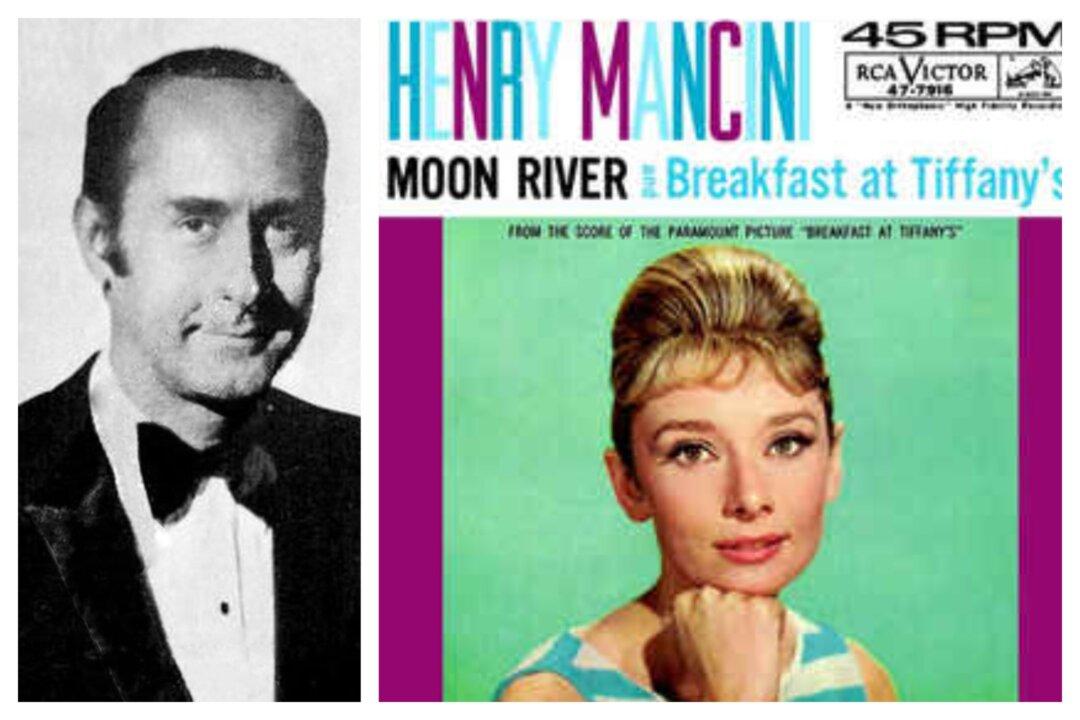

He longed to paint pictures with his music—and, in the process, he transformed the way that music was scored in films, spinning his own brand of unorthodox instrumentation and sophisticated, melodies. Henry Mancini incorporated popular music traditions into his productions, as well as a fair share of offbeat effects, bridging his classically trained awareness with a sharp ear for the instrumentalism of contemporary pop.

The career highlights of Mancini as composer and arranger of movie songs, film scores, and TV show soundtracks and themes are many. From “Moon River,” the timeless hit from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” to the sly score for “The Pink Panther” series; to the musical scores for “The Glenn Miller Story,” “The Benny Goodman Story,” and “The Glass Menagerie”; as well as TV series soundtracks ranging from “Peter Gunn” to “Newhart”; his trail was prodigious.