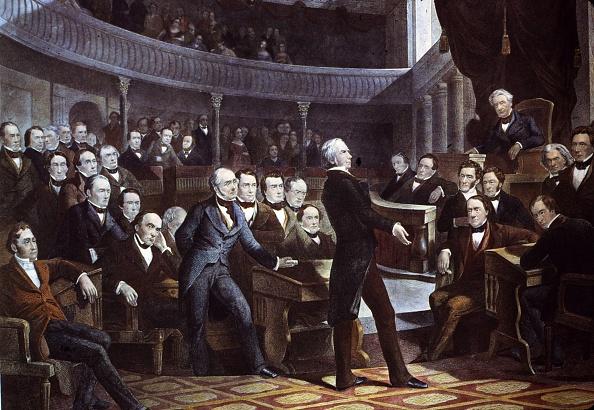

Known as “The Great Compromiser,” Henry Clay would use his stellar public-speaking skills to rise through the political ranks and influence many major decisions of our country. Although never president, despite several tries, Clay would make a name for himself as a senator and speaker of the House of Representatives. He was named one of the country’s best senators of all time in a 1957 Kennedy special selection committee.

When Clay spoke, he would draw large crowds who leaned toward every word he said. His oratory skills enabled him to succeed in several attempts to come to a compromise. Clay tried hard to hold the Union together in the decades before the Civil War, and some have even said that the war would not have happened had Clay lived another 10 years.