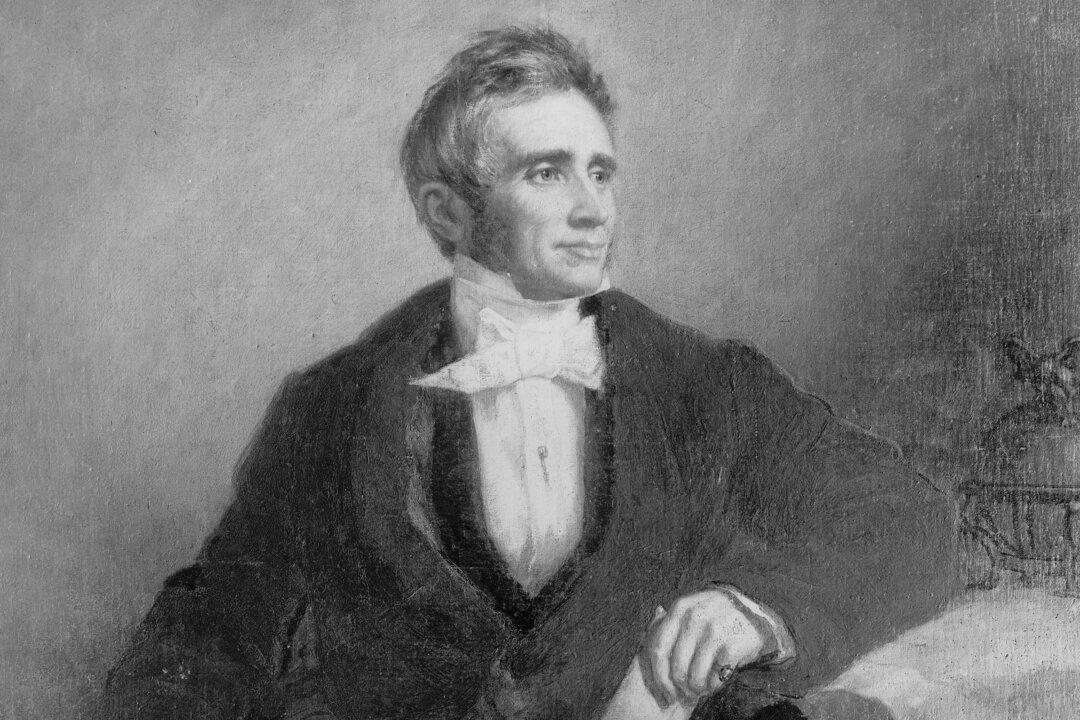

Henry Bergh didn’t seem like the sort of person who would commit his life to protect countless creatures. The son of a wealthy shipbuilder, he led a life of leisure and inherited prosperity and had little experience in public service. He'd never even owned or had a pet.

However, after witnessing the harsh lashing of a horse, too many workhorses thrashed, and too many dogs chained to treadmills for labor, he became a campaigner for the defenseless—a one-person champion of animal rights—ultimately founding the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA).