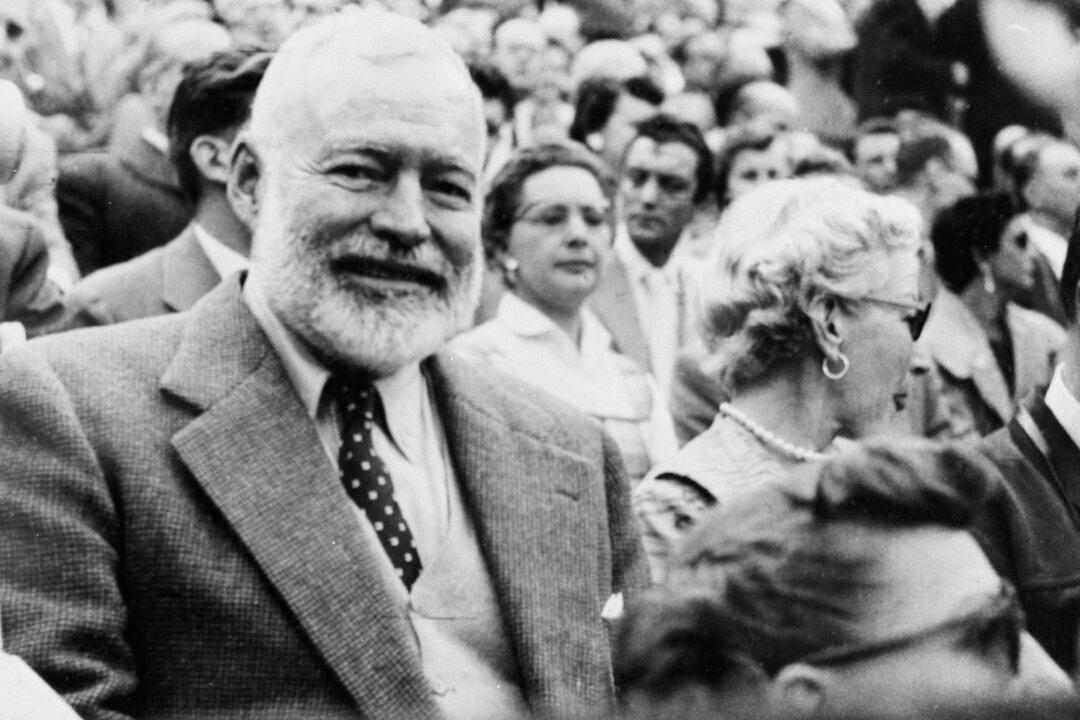

The show “Hemingway: Between Two Wars“ at the Morgan Library in New York focuses on the years between World War I and World War II and explores the most creative phase of Hemingway’s career. It also includes multiple drafts of his earliest short stories and several manuscripts of his major novels, as well as correspondence with the group of expatriate writers in Paris. The show reminded me of an article by Gabriel García Márquez where he describes his encounter with Ernest Hemingway:

“I recognized him immediately, as he passed with his wife Mary Welsh on the Boulevard St. Michel in Paris one rainy spring day in 1957. He walked on the other side of the street, toward the Luxembourg Gardens, wearing a worn pair of cowboy pants, a plaid shirt and a ballplayer’s cap. The only thing that didn’t look as if it belonged to him was a pair of metal-rimmed glasses, tiny and round, which gave him a premature grandfatherly air. For a fraction of a second, as always seemed to be the case, I found myself divided between my two competing roles. I didn’t know whether to ask him for an interview or cross the avenue to express my unqualified admiration for him. But with either proposition, I faced the same great inconvenience. I spoke the same rudimentary English I speak to this day, and I wasn’t very sure about his bullfighter’s Spanish. And so I didn’t do either of the things that could have spoiled that moment, but instead cupped both hands over my mouth and, like Tarzan in the jungle, yelled from one sidewalk to the other: ‘Maeeestro!’ Ernest Hemingway understood that there could be no other master amid the multitude of students, and he turned, raised his hand and shouted to me in Castilian in a very childish voice, ‘Adiooós, amigo!’ It was the only time I saw him.”

García Márquez thus expressed his appreciation for one of the two authors who most influenced his work (the other was William Faulkner). But Hemingway also influenced countless generations of writers, including many from Latin America and the Caribbean.