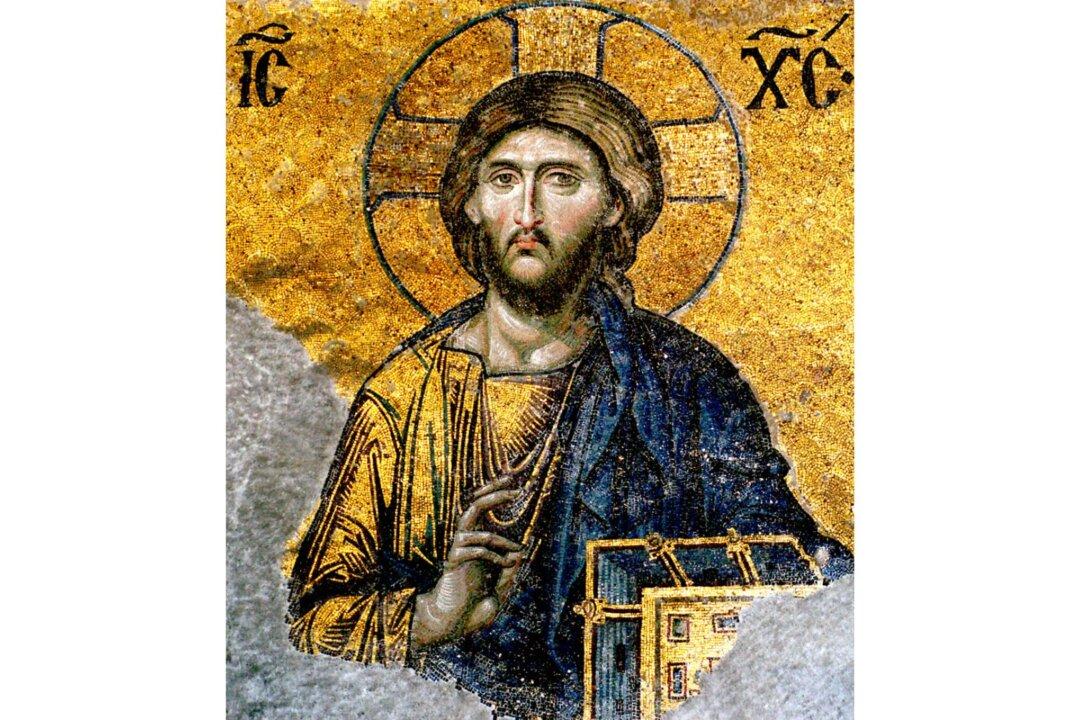

We’ve lost a world of Byzantine art and architecture throughout history, yet what remains reminds us of a culture steeped in spiritual values and traditions.

It all began in 330, when Emperor Constantine established the Eastern Roman Empire in Byzantium, a city on the shores of the Bosphorus Strait, midway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea, where Asia and Europe meet. He renamed it Constantinople, now known as Istanbul.