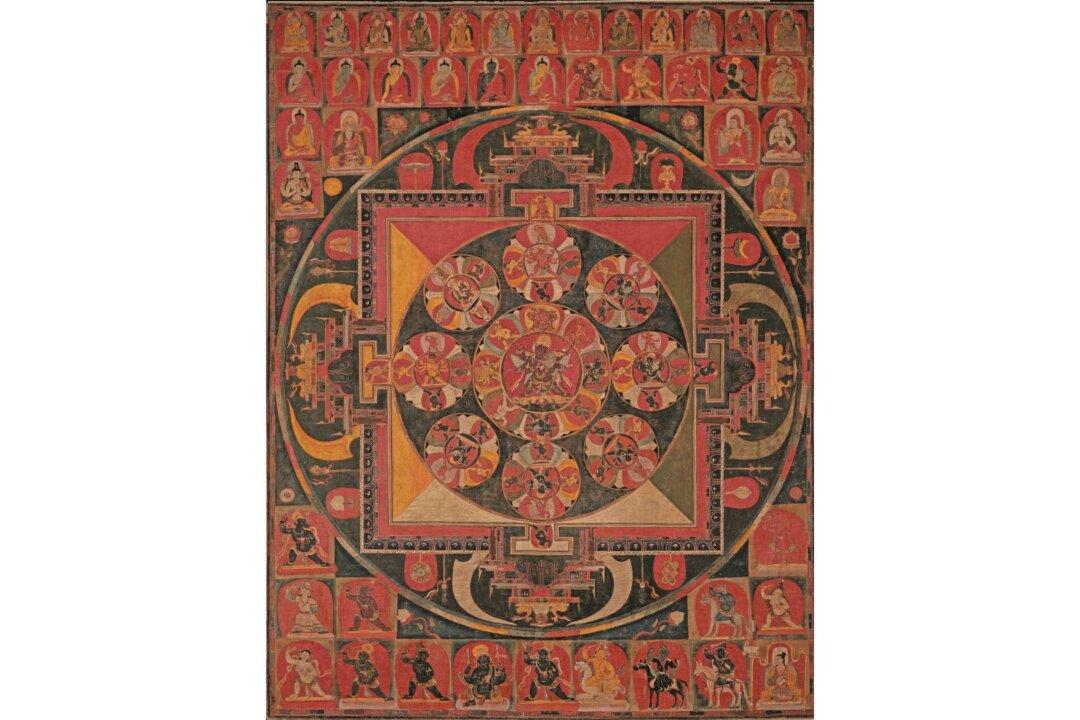

Many religions believe in a heavenly paradise, free from the pain and suffering of life on earth. Throughout history, artists have imagined hidden higher realms, giving us a glimpse of what it might be like to reach our salvation.

Visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, can enjoy a pantheon of jewel-colored gods and deities in rare Tibetan Buddhist art. Its “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet” exhibition explores the secretive world of Himalayan Buddhist sacred art through some 100 paintings, sculptures, and ritual objects, including textiles, costumes, weapons, and musical instruments. Kurt Behrendt, the museum’s associate curator of South Asian art, curated the exhibition.Most of the exhibits date from the 11th century to the 15th century and were made for private devotion—not public display.