NEW YORK—Harvey Dinnerstein waited at the bottom of the stairs of his Brooklyn brownstone, contemplating the darkness of the interior space. Since a broken washing machine flooded his home nearly a year ago, there has been no electricity and no water. The rooms were gutted, save for his studio on the top floor. We walked up the dim stairwell, past narrow hallways that doubled as storage space for his life-size portraits and large figure paintings. At the top, in the studio, diffused light filtered through a skylight, casting soft shadows on the space overflowing with paintings, with only small passageways to walk through.

Dinnerstein took the flooding in stride. None of his paintings were damaged, and reconstruction would finally be starting the next day. He plans to continue painting in a temporary residence a mile away until his home is fully renovated. In the meantime, the Brooklyn-born artist (1928) has deeper issues and questions to ponder.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2268234,2268235,2268241”]

In a supplement to the latest retrospective of his work, “Underground Together: The Art and Life of Harvey Dinnerstein,“ he wrote: ”Time moves inexorably. Another turn of the wheel, and I find myself in this ninth decade of my life, contemplating past and present.”

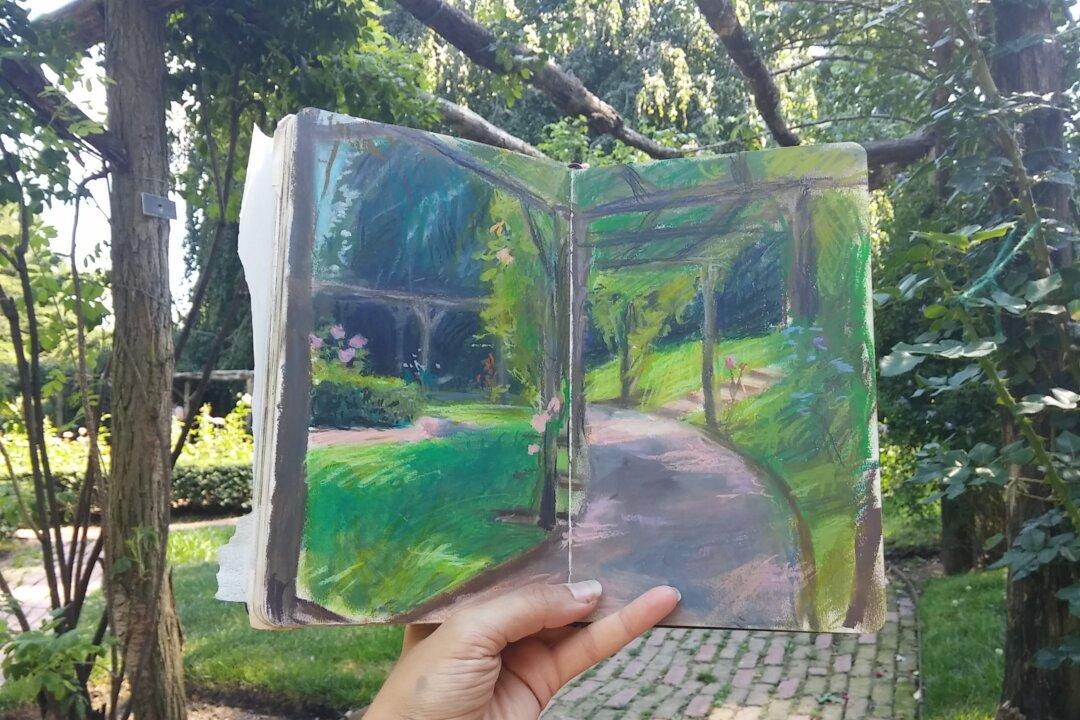

A leading figurative painter, Dinnerstein’s oeuvre bridges the 20th and 21st centuries. In retrospect, he realizes that he keeps revisiting familiar themes—intimate scenes of his family, his wife, and himself, everyday city life, the seasons, and mythic conceptions. He revisits these subjects and themes not to repeat them, he said, but hopefully to bring in other perceptions that interest him.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2269092,2269096,2269108,2269110,2269100”]

His paintings evoke universal qualities of humanity—birth, life, and death—and bring up timeless questions: Who are we? Where did we come from? Where are we going? They depict the human condition, the rich variety of people, and their particularities, as seen through his eyes.

Dinnerstein didn’t want to talk specifically about what he is currently working on. Without missing a beat, he said, “Of course, if I talk about it, I won’t do it.”

While his paintings speak for themselves, he readily shares his creative process in great detail with his students and in books written about his work. He also talked at great length about the interwoven aspects of his paintings in a lecture he gave at The Academy of Art University in San Francisco in 2009, which can be viewed on YouTube (ept.ms/DinnersteinTalk).

A Realist With Thirsty Eyes

Dinnerstein survived as a realist artist through the height of modernism in the 1940s, abstract expressionism in the 1950s, and the various ensuing forms of postmodernism. He was not alone. He grew up and studied with precocious kids who became lifelong friends and serious artists. They learned from each other, studying great masters in museums as opposed to the modernist theories and Bauhaus methods of instruction that dominated art schools at the time.

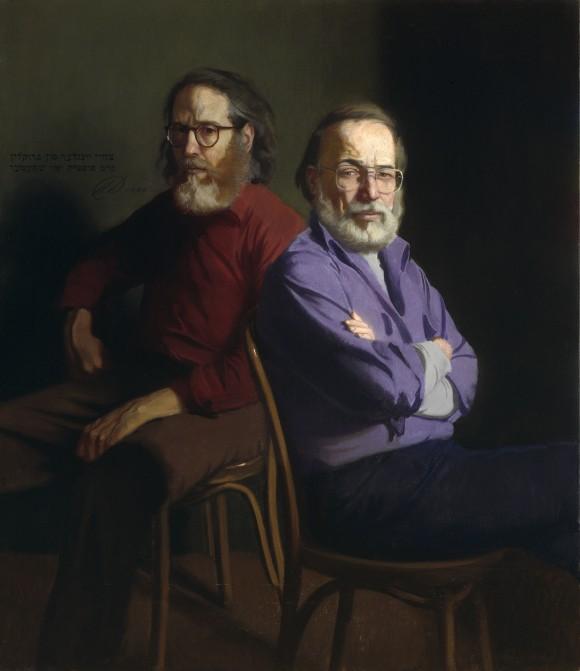

“Somehow, time erases, and there is a fragility to everything that I’m especially aware of as I get older,” Dinnerstein said, “so I like to mention their names to remind people.” He mentioned eight of his artist friends who are no longer with us—Herb Steinberg, Robert White, David Levine, Aaron Shikler, Sheldon “Shelly” Fink, St. Julian Fishburne, Stuart Kaufman, and Seymour Remenick—and the two who continue to paint today, Daniel Bennett Schwartz and Dinnerstein’s friend of 75 years, Burton Silverman.